Abbey Church of St. Denis, Paris

St. Denis is thought to have been a Bishop of Paris, who lived in the 3rd Century, who was sent to Gaul to convert the people to Christianity. He and his companions, Rusticus and Eleutherius, were martyred for their faith, after being beheaded by a sword. He is thought to have been killed during the persecution of Christians by the Roman Emperor Decius, this is why he is often depicted with his head in his hands. The first Abbey of St. Denis was founded in the 7th Century, by King Dagobert (629-639). It was built over the tomb of St. Denis, who is the patron saint of France.

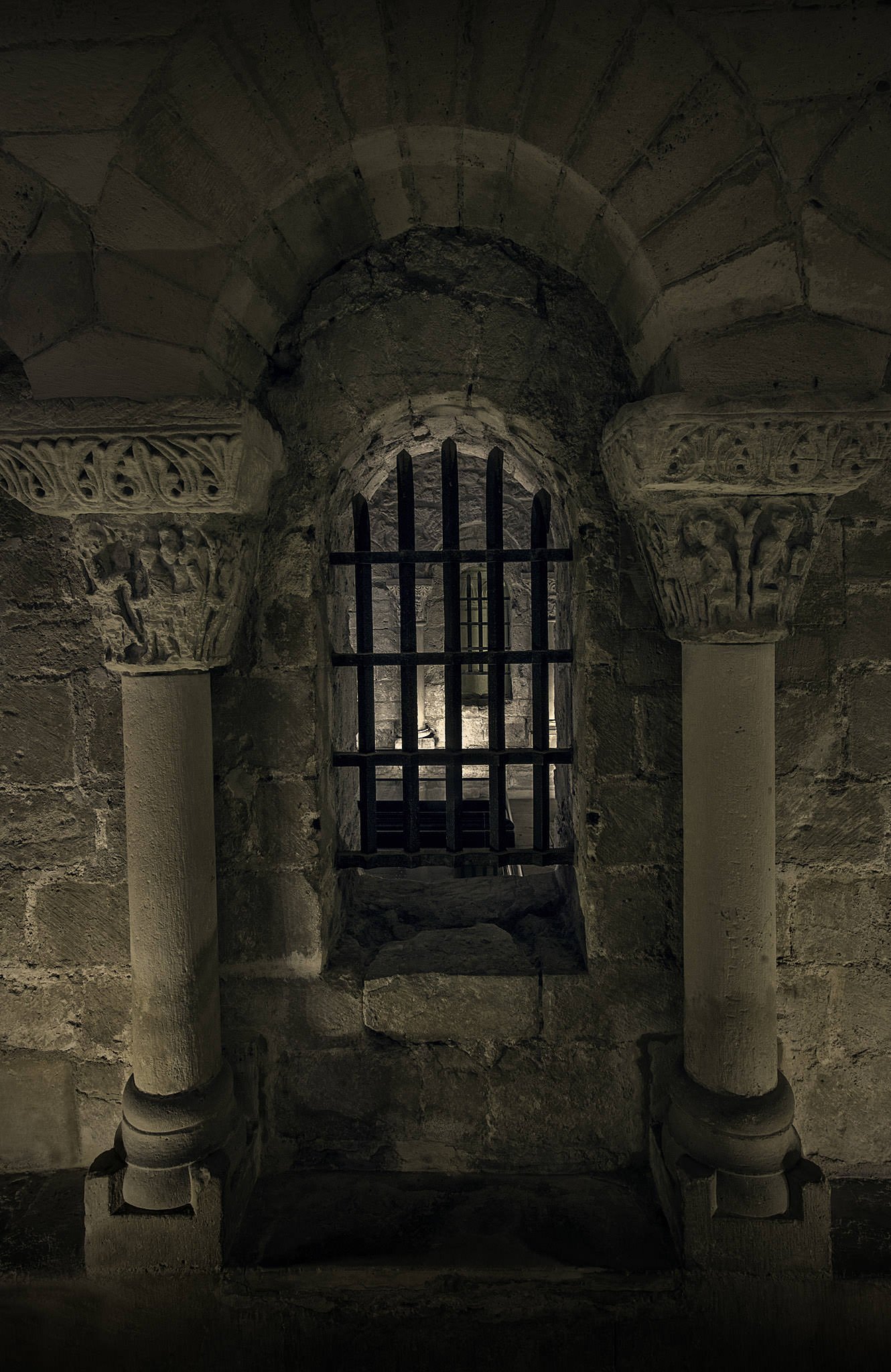

By 1100, rib vaulting was already in use in England and in Italy. This creates crisscross lines of penetration, which are underlined by a system of ribs, clearly dividing the surface of the vault into triangular sections. With rib vaulting, the weight is channelled to the ground along the pillars and columns, so that the space can be opened up and greater heights achieved. By 1125, this system of diagonal ribs was adopted in Normandy. The pointed arch had also been known to Romanesque builders, before the end of the 11th Century. It had been used first in Islamic architecture of the near east in the 8th Century, and was in use through Egypt, Tunisia and Sicily under Arab rule. The exact course of its migration to Western Europe is not certain, but it is certainly speculated upon. Depending on what countries documents you are reading, you can find an argument for the pointed arch being used first in most Western European countries. One suggestion, is that it was first used in Sicily, before the conquest of the island by the Normans, in the late 11th Century. It is also thought to have been used at Cluny, in Burgundy, in the new church in 1088, but this was in large part destroyed during the French Revolution. By the 1130’s, it is widely thought that the pointed arch had spread to many parts of France, Burgundy, Provence, Poitou, Aquitaine, Paris, and some parts of England. There is an abundance of evidence that the pointed gothic arch was in wide spread use by the 1130’s, and yet it is also widely claimed, that St. Denis in Paris was the birthplace of Gothic.

Perhaps we have to split the idea of Gothic architecture, from the pointed arch itself. Gothic rose out of the world of the Romanesque, and this new style of gothic is widely claimed to have originated in Paris around 1140. St. Denis in Paris is still proclaimed as the parent of all gothic cathedrals. While it can certainly be argued that the pointed arch did not originate in France, the ideas of gothic itself seems to have. The first Gothic age produced the Cathedrals of Notre Dame in Paris, Laon, Chartres, Bourge, Reims, Amiens and Beauvais. By the mid 12th Century, gothic had become a vital movement and expression, it had made great leaps in both artistic and technical innovation. Gothic continued its evolution, with new generations of builders who achieved new ideas, they made advances in the mechanics of stone construction, that allowed more light to enter a building, and more space was created. It is that idea of pushing the boundaries, opening the space, which originated in France. Limiting this invention to the pointed arch, is missing what Gothic truly is. The use of the pointed arch, simply provided the physics that allowed them to create new rules of construction.

John Henry Parker wrote a book called 'Gothic Architecture’, which was published in 1870, where he clearly proposes after his 30 years of study, that the style of Gothic did not originate in France at all, but instead originated in England. He argues, that the parts of St. Denis which were built by Abbot Suger, were not those which are gothic at all. He goes on to state that the parts of Canterbury Cathedral, which were built by William the Englishman (1186-1183), are more advanced in the Gothic style than the parts of St. Denis, built by William of Sens under Suger’s instruction (1140-1145). This shows clearly what history always teaches us - the more we think we know, the less we really do. There is, almost always, something that will challenge the very facts we have come to rely on. I can’t say if John Henry Parker is correct, but it is certainly interesting to read his thoughts.

King Louis VI of France, first met the soon-to-be Abbot Suger, when they were both students, attending the monastic school at the Abbey of St. Denis, just outside Paris. Although Suger was of a much humbler status than the Dauphin Louis, these lines were often blurred in a monastic scholarly setting. They became friends at a young age, a friendship that would last a lifetime. Suger was born in 1081, when King Philip I was King of France, he came to the monastic school at St. Denis at the age of 10. In 1106, Suger took his vows as a monk, and from the start he is said to have showed a fairness that was often lacking in church administration. He was given the task of administrator of St. Denis, which meant it was his responsibility to investigate and alleviate financial troubles, in the districts under the Abbey’s control. The Abbey was the owner of many land holdings, and as such would be entitled to a percentage of anything made or grown on its lands. However, many of the local clergy were not as fair, and peasants were often allowed to keep only a small portion of the food they laboured to create. Suger discovered that formerly prosperous areas, suddenly reduced contributions to St. Denis, because the local church officials were demanding too much from the people in its parish. He addressed this by reducing their obligations. He also showed his ideals of fairness later, when he led a peasant army against a Baron who had been looting farms. Suger appears to have acted in good faith, when new property was acquired, it was rented at fair prices. Suger embarked upon a program of reconstruction and rehabilitation of old buildings, measures were taken against reckless deforestation, tenants were settled in many places, so as to transform cornfields and vineyards from what had been once wasteland, however, many of his biographers were also his fans, so we have to be careful in raising him overly high. However, his diplomatic skills lead to his appointment, by his friend King Louis VI, as Ambassador to the Pope. In 1122, at 40 years of age, he was appointed as the new Abbot of St. Denis.

In 1124, King Louis VI made his way from the Palace to the Abbey of St. Denis, upon the news that the country was about to be invaded, by the alliance between the English King Henry I and Henry V, Emperor of Germany. King Louis went to pray at the shrine of St. Denis, who was thought to be the protector of France. He also went to consult with his friend, Abbot Suger, on the matter, as he was unprepared for battle. He also pledged a generous donation to the Abbey, if France was delivered safely though these troubled times. Abbot Suger wisely advised the King not to engage the invading army with his weaker forces, but instead counselled the King to call an assembly of the most powerful churchmen and landowners in France, asking for a supply of money and men. France was at this time only a small country, and not what it has become today, but Suger had a plan. While the King would prepare for war, Suger would sell the war, to the French people, as being against St. Denis himself, and against everything French. Suger turned the invasion into a Holy War, and involved Pope Calixtus II, a man who originally was from Burgundy, and whose sympathies would lie with France. His diplomacy united the French against a common enemy, and the attacking forces dissipated. Bloodshed was avoided, and Suger had proven himself a worthy opponent and successful diplomat. Abbot Suger became, after the King, the most powerful man in France. King Louis VI was also a man of his word, and although a battle had not been fought, the King still considered himself victorious and he donated a fortune to the Abbey of St. Denis, which he proclaimed to be the religious capital of the Kingdom, also awarding it an annual income.

The Abbey of St. Denis now had the most popular shine in France, but in the early 12th Century, it didn’t look the part. The religious buildings were old, small and run down. The Abbey also had other relics to look after - it was said there was a nail from the true cross, and a thorn from the Crown of Thorns. All these relics attracted pilgrims, who brought with them financial offerings that the Abbey needed. The popularity of these artifacts drew such great crowds, that on several occasions, bystanders were trampled to death, by mobs stampeding to pray before the relics. I won’t even comment on that. The volume of visitors were also a threat to the building itself, which was not large enough to accommodate them. By the mid-12th Century, Abbot Suger believed that it was his job to create a new church, to both house the relics, and better service the brethren of the Abbey. It is thought that he possessed an unusual combination of piety and worldliness, he was smart and savvy, he was well travelled and powerful, and he now had the funds and position to transform the Abbey of St. Denis. He wanted to rebuild portions of the Abbey Church, and chose to use innovative structural and decorative features to achieve this, and in 1125 he announced his intention.

Although funds were gathered, Suger delayed the start of the building works, it is unknown for what reason, but a ceremony did finally mark the occasion of the start of construction, which began with the new choir on the 14th of July 1140. This was attended by King Louis VII, courtiers, Archbishops and priests, who encircled the site and walked through the foundation trenches, singing the 86th Psalms. It was said that King Louis VII removed his ring and tossed it into the mortar which would be used to join the stones, others followed suit, tossing their jewellery into the mortar.

Abott Suger’s announcement to rebuild the Abbey of St. Denis, received an overwhelmingly positive response. He was given gifts of money, land, and jewels. Pilgrims with no money would offer their labour. Always the businessman, Suger relieved the town of St. Denis from their tax obligations, and the townspeople were so moved, that they took up a collection for the building work. Suger did not just hire a master mason to build his new church, he oversaw the construction himself, which was unusual at the time. He selected the stone and wood himself, which Suger describes in his writings:

‘I began to think in bed that I myself should go through all the forests in these parts…Quickly disposing of other duties and hurrying up in the early morning, we hastened with our carpenters, and with the measurements of the beams, to the forest called Iveline. When we traversed out possessions in the valley of Chevreuse we summoned the keepers of our own forests as well as those who knew about the other woods, and questioned them under oath whether we could find there, no matter with how much trouble, any timbers of that measure. At this they smiled or rather would have laughed at us if they had dared; they wondered whether we were quite ignorant of the fact that nothing of the kind could be found in the entire region… However, we began with the courage of our faith as it were, to search through the woods; and toward the first hour we had found one timber adequate to the measure. By the ninth hour or sooner we had, through the thickets, the depths of the forests and the dense, thorny tangles, marked down twelve timbers’

Suger would later be credited with creating the Gothic movement, which swept through and defined, the greatest buildings of Europe. This was certainly not what he set out to achieve. His one and only plan, was to build a church that was worthy of St. Denis. It was only shortly after he was appointed as Abbot, that he embarked on his plans for his new church. An extravagance which prompted his receipt of a letter from Barnard of Clairvaux, the founder of the minimalistic Cistercian order. Suger moderated his ways, to a point, he was clearly intelligent and learned how to work within the system. He and Barnard of Clairvaux became friends, even if they often disagreed. Suger wrote that:

‘As for myself, I declare that it has always seemed right to me that everything which is most precious should above all add to the celebration of the Holy Eucharist. If golden cups, golden phials and small golden mortars were used, in obedience with the Word of God and by the command of the Prophet…Should we dispose of the golden vases and precious stones and all that creation holds most valuable? Those who criticize us claim that this celebration needs only a holy soul, a pure mind and a faithful intention. We are certainly in complete agreement that these are what matter above all else. But we believe that outward ornaments and scared chalices should serve nowhere so much as in our worship, and this with all inward purity and all outward nobility.’

Suger’s importance as a diplomat cannot be over stated, he was one of the most trusted advisors to the King, Louis VI. When Pope Innocent II sought refuge in France, it was Abbot Suger who was appointed by the King to receive him. A few months before King Louis VI of France died, he visited Abbot Suger at St. Denis, and prayed in the crypt, in the burial chapel of the kings of France under the present choir.

In 1137, Abbot Suger’s lifelong friend, King Louis VI of France died, leaving his young son King Louis VII as his heir. He, along with his new wife, Eleanor of Aquitaine, would now rule France. Abbot Suger retained his position as a trusted advisor to the new King. When King Louis VII went on the Second Crusade to the Holy Land, in 1147, Suger was named as regent of France, while the King was away for more than two years. While western Europe would like to take complete credit for Gothic Architecture, it is often forgotten that it was the second crusade, of the 12th Century, that inspired it. The crusaders returned home with reports of architecture, which they said was more impressive than anything they had seen in Christendom. The pointed arches, and slender columns, which seemed to reach forever upwards. Abbot Suger, being Regent at this time, would certainly have spoken to men who had gone on Crusade, and with his mind once again thinking of his new church, it is highly likely that some of the images described to him, were incorporated into the new building.

In designing the new church, Abbot Suger created a place of symmetry, its ideas built on basic geometric shapes, with circles, squares and triangles, which repeated themselves with a duplicative effect, that was both grand and subtle. He was also interested in light, believing that the divine intellect illuminated the human mind, and that the physical light he could create in the church, would lead the way to the mystical light of God. He wrote:

‘The church shines with its middle part brightened. For bright is that which is brightly coupled with the bright. And which the new light pervades. Bright is the noble work enlarged in our time. I, who was Suger, have been leader while it was accomplished.’

Gothic itself was finding its way, and while the previously used rounded arches produced the half cylinder shape, their construction created a heaviness of stone, and greatly increased the natural thrust of all vaulted structures. To build higher and prevent the thrust of the vaults from pushing the walls downward or outward, the builders began to brace the exterior of the walls with vertical supports, known as buttresses. The buttress was adapted by Gothic builders, and it became a distinguishing aspect of the Gothic period, although it may be lesser known than the ribbed vault or the pointed arch. The three together became the signature elements of the Gothic style, which were joined later by a variation of the buttress, known as the 'flying buttress’, because it would not be attached to the building directly, but via a decorative feature which would support the building. The pointed arch had the significant advantage of being stonger. It transferred the weight in a different way, more of the weight was pushed downwards, rather than outwards. With the use of pointed arches, builders were now able to support the weight with a series of piers. These piers, or supporting columns, were much less bulky than would have previously been required in Romanesque barrel vaults. Ceilings could now be built higher, and the use of rib vaulting now allowed more slender support columns, so the walls of the building would now be pierced with windows allowing more light to enter.

On the 11th of July 1144, Abbot Suger’s new church, although not finished, was dedicated with a grand ceremony. The King, Louis VII, was in attendance accompanied by his Queen at the time Eleanor of Aquitaine, and many of the nobles. The dedication ceremony seems to have inspired the same enthusiasm as the foundation ceremony. The King was said to have been particularly pleased, and even Bernard of Clairvaux was in attendance. Although he had sometimes criticized Suger for his lavishness, he praised the building. Suger was not allowed to boast of his accomplishments but he had inscribed over the entrance door:

‘Marvel not at the gold and the expense, but at the craftsmanship of the work,

Bright is the noble work; but being nobly bright, the work should brighten the minds, so that they may travel, through the true light,

The dull mind rises to truth through that which is material.’

The rebuilding work in the choir was done between 1140-1144, and it was upon this completion that the dedication, or consecration, celebration took place. After the dedication, word of the new church of St. Denis quickly spread throughout France. At the time, nobody called it gothic, that term wouldn’t be used for hundreds of years. When the term Gothic was first used, during the late Renaissance period, it was used as an insult and reference to the barbaric Goths who had overrun Rome. At this time, the new style was known as ‘Novum Opus’, meaning new work. They would have been better off using a word like ‘recreated’, as nothing was really new, the same wood, stone and lime were still being used, but now they had a new way of using them. Many of the old materials, from older buildings, were being recycled into new Gothic style buildings. This new way of combining materials into the ‘gothic’ fashion, would go on for hundreds of years.

Abbot Suger had two ambitions in his life, both of which he was successful in achieving. He wanted to strengthen the power of the Crown of France, and he wanted to improve the Abbey of Saint Denis. For Suger, these ambitions did not conflict with each other, but were simply separate aspects of one ideal, in which he wholeheartedly believed. He believed that the King of France, and in particular his personal friend King Louis VI, was God’s representative, and as his friend the King had invested him with the ‘defence of the church and the poor' at his coronation, he felt he had a sacred duty to unify the nation whose symbolism was vested in the Abbey of St. Denis. Suger never ceased to promote the interests of the Abbey of St. Denis, and he completely believed this was in alignment with the will of God. He believed that material beauty could be used as a vehicle for spiritual beatitude. Instead of being forced to flee from its temptations, as the Cistercians and Barnard of Clairvaux professed, he felt it would bring people into the church itself, and over time he was proved to be correct. No matter what anyone’s spiritual beliefs are, or lack thereof, the Abbey church of St. Denis does bring in visitors, even today.

Suger would later write about the new church he would create, and we see Suger walk the diplomatic tightrope in his writings. In the 12th Century, churchmen were supposed to live a simple life of self-discipline and personal sacrifice, and all the other churchmen around them were watching them. Abbot Suger followed this, but he also loved the extravagant and the beautiful. Suger was a powerful man, and yet he absolutely felt he needed to justify everything he created. Nothing was for him, nothing his idea, it was all God’s plan, done through God and with his approval, and we see this repeatedly in his writings. Even the very idea of writing down what he created, he could not take the credit for, although you don’t get the impression that they had to twist his arm, he tells us that:

‘In the twenty-third year of our administration, when we sat in the general chapter, conferring with our brethren about matters both common and private, these very beloved brethren and sons began strenuously to beseech me in charity that I might not allow the fruits of our so great labours to be passed over in silence; and rather to save for the memory of posterity in pen and ink, those increments which the generous munificence of Almighty God had bestowed upon this church, in the time of our prelacy, in the acquisition of new assets as well as in the recovery of lost ones, in the multiplication of improved possessions, in the construction of buildings, and in the accumulation of gold, silver, most precious gems and very good textiles….We thus devoutly complied with their devoted and reasonable requests, not with any desire for empty glory nor with any claim to the reward of human praise and transitory compensation.’

Abott Suger’s writings have a bit of flourish about them, but he is trying to, in his own way, document his life’s work, the rebuilding of the Basilica of St. Denis. He clearly tells us, how important this was to him, and it is pretty amazing that his writings have survived. In the mid 12th Century, he writes that:

‘because of the age of the old walls and their impending ruin in some places, we summoned the best painters I could find from different regions, and reverently cause these walls to be repaired and becomingly painted with gold and precious colours. I completed this all the more gladly because I had wished to do it, if ever I should have an opportunity, even while I was a pupil in school.’

At times, in his writings, it seems that Suger almost ties himself in knots trying to not take credit for any of the construction:

‘We hurried to begin the chamber of divine atonement in the upper choir where the continual and frequent victim of our redemption would be sacrificed in secret without disturbance by the crowds. And, as is found in our treaties about the consecration of this upper structure, we were mercifully deemed worthy -God helping and prospering us and our concerns – to bring so holy, so glorious, and so famous a structure, to a good end, together with our brethren and fellow servants; we felt all the more indebted to God and the Holy Martyrs as He, by so long a postponement had reserved what had to be done for our lifetime and labours. For who am I, that I should have presumed to begin so noble and pleasing an edifice, or should have hoped to finish it, had I not, relying upon the help of Divine mercy and the Holy Martyrs, devoted my whole self, both with mind and body, to this very task? But he who gave the will also gave the power; because the good work was in the will therefore it stood in perfection by the help of God.’

Abbot Suger fell ill with a fever, in the autumn of 1150. In his own theatrical way, he asked to be led to the brethren, and while weeping implored the monks to forgive him for everything, in which he might have failed the community. But he also prayed to be spared, until the end of the festive season

‘lest the joy of the brethren be converted into sorrow on his account.’

His wish was granted, and he survived until the 13th of January 1151, when he took his last breath.

I will not go too far into Suger's writings, as he does tend to go on a bit, but his description of the creation of a new shrine to house the relics of St. Denis is, to my knowledge, unique in its existence. But to anyone interested, Suger’s writings have been translated into a book titled, “Abbot Suger: on the Abbey Church of St. Denis and its Treasures”. He described moving the body of St. Denis as follows:

'Since it seemed proper to place the most sacred bodies of our Patron Saints in the upper vault as nobly as we could, and since one of the side tablets of their most sacred sarcophagus had been torn off on some unknown occasion, we put back fifteen marks of gold and took pains to have gilded its rear side and its superstructure throughout, both below and above with about fourty ounces of gold. Further we caused the actual receptacles of the holy bodies to be enclosed with gilded panels of cast copper and with polished stones, fixed close to the inner stone vaults, and also with continuous gates to hold off disturbances by crowds; in such a manner, however that reverend persons, as was fitting, might be able to see them.'

The Basilica Church of St. Denis was rebuilt, almost completely, between 1136 and 1270. Its dimensions are 108 meters (354 feet) in length, 39 meters (127 feet) width, and 86 meters (282 feet) in height. The first phase of the rebuilding work started at the west front, which was built 1135-1140. The west front is divided into three sections, with the central section being the largest. This clear, vertical, division into three, became a common element in the development of Gothic architecture. It is also interesting to note, that art students are taught that things in triplicate are more pleasing to the human eye. There were once two towers on the west front, of which only one remains. The second and larger, missing tower, was dismantled in 1846, after storm damage and a botched attempt to rebuild it.

The second phase of building work at the church, was the east end. This was begun in 1140, and it is here that we see all the new elements of the gothic style of architecture being combined. It is thought that this may have been the result of Suger’s fascination with light, but that is probably conjecture. When you look back to the 12th Century, the absolute truth is an impossibility, just as today, people wrote and said what was expected of them. They had their own thoughts and motivations, but their words and actions is all we have to go on, and we can only surmise their intentions. Suger may have picked his wood and stone, but he did not cut and install it himself. While given the credit, the people who actually did the work are virtually forgotten, their names unknown, and it may well have been a master mason who came up with the ideas that made Suger’s church come together. However it all came together, the rebuilding of the choir, at the east end of the church, may well be the first time that the elements of gothic architecture, the pointed arch, the ribbed vault and the buttress worked together as one. All three of these elements had previously existed independently in building techniques, but their combination at St. Denis, is why it has come to be known as the birthplace of Gothic.

After Suger’s death, the work on the Abbey church stopped, and it did not resume until 1231. The nave of St. Denis, with its massive slender windows, was not completed until 1281. The church remained virtually unchanged from then, until the 18th Century. Throughout its history, St. Denis has been closely associated with the Royal House of France. Since the reign of Dogobert I, in the 7th Century, almost every French King has been buried in the Basilica of St. Denis. In total, 42 Kings, 33 Queens, 63 Princes and Princesses, and 10 nobles of France, are buried in St. Denis, not to mention the Bishops and Abbots who are also there. With the Abbey of St. Denis being the burial place of the Kings of France, I could have gone down the story of any of their lives and it would have filled this section, but with so many, there was no way to choose, so it seems to make sense to me to focus on Abbot Suger, who was the primary creator of the church. However, before I close this section, I don’t want to completely leave out all the burials which took place here.

For 1200 years, with a few exceptions, the Kings of France have been buried at Saint Denis. There are more than 70 effigies in the basilica, and the church is considered today to be the most important assembly of funerary sculptures, which date from the 12th to the 16th Centuries. The funeral effigies of Francis I of France, or Henry II of France and Catherine of Medici, and Louis XII and Anne of Brittany, as well as lesser-known figures, reside here. The dynasties of the Merovingian, Carolingian, Capetian, Valois, Valois-Angouleme and Bourbon, reside in St. Denis.

The tomb of Louis XII and Anne of Brittany, may be the largest in St. Denis Basilica. The tomb was commissioned in 1515, after the death of Louis XII at the age of 52. His Queen, Anne of Brittany, had died one year previously, at the age of 36. The tomb was unveiled in 1531, and represents a distinctive change in style from the medieval effigies that were seen previously, where the focus is on a depiction of a single person. It is a unique interpretation of the cadaver tomb. Although the interior of the tomb does show this, above, King Louis is seated, with his Queen, Anne, kneeling, and both have their hands clasped in prayer. The arches of the tomb contain a number of statues which depict the apostles, and the seven cardinal virtues.

On 31st of July 1793, during the French Revolution, it was decided that all the royal tombs would be opened and destroyed. This reminder of the Ancient Regime was not only desirous to be rid of, but it was thought that the tombs may contain valuables, and the Revolution was in need of money. Some of the larger monuments were removed first, and many of the old graves were opened. Among them were the graves of Philippe III of France (1245-1285), Pepin the Short, who reigned (751-768), and Queens Isabelle d’Aragon (1248-1271) and Constance de Castille (1136-1160), as well as Louis VI (1081-1137).

In October of 1793, the desecration of the Abbey of St. Denis’ tombs continued, with more recent tombs being opened. As they opened these graves, they also removed everything of value, including the lead from the coffin itself. The remains of the deceased were collected, and tossed into a large pit outside, which was covered with slaked lime. The destruction continued through January of 1794, with many more graves of Kings, Queens and nobles being desecrated. However, some of the monuments, which were thought to have been skilfully made, were transferred to the Musee des Monuments Francais.

The funeral statues of Marie Antoinette and King Louis XVI of France, were commissioned by Louis XVIII, in 1815. Different sculptors were chosen for each of the statues, with Pierre Petiotot creating the statue of the Queen, and Edme Gaulle creating that of the King. Petitot completed his statue in 1819, however Gaulle did not finish his work on the King until 1831. The statues were originally located in the crypt but were moved in 1975, to their current location in the Saint-Louis Chapel.

The Abbey was saved by Napoleon Bonaparte, who appointed Francois Debret to restore the church to its former glory. Debret was more interested in creating something than restoring it, and what he created was a feeling of medievalism, but that did not return what had been lost. He was eventually replaced by Eugene Emmanuel Voillet-le-Duc, who did what he could to fix Debret’s mistakes, and his, more accurate reconstruction, is what we see today.

When it comes to the funerary monuments at St. Denis, it is difficult to work out how many of these monuments are authentic, and how many have been re-created. It does appear that most of what we see today, are the monuments which were not destroyed, but moved to the Museum of Monuments, but I have not taken this on a case-by-case basis. The monuments, which had been sent to the Musee des Monuments Francais, were returned to St. Denis in 1816, and established in the crypt. This brought tourists to St. Denis, and is thought to have helped to ignite an interest in the Middle Ages. In 1828, two altars were created on each side of the choir, and the monuments were moved from the crypt to their current locations.