Barley Hall York, England

Barley Hall in York, is unlike any other medieval building. The York Archeology Trust set out to preserve a medieval house, so that visitors to the city could see how people lived in the middle ages. Barley Hall, when discovered to be a medieval house in the 1980’s, was in a hazardous and nearly ruinous state. It has been completely restored and in most cases rebuilt, using traditional medieval methods, to recreate the medieval house as it once had been. This has been a resounding success. Barley goes one step further and teaches the visitor about the daily life of people in medieval York.

Excavations in the 14th Century great hall, found elaborate sets of glazed tiles, which had surrounded a central hearth. Samples of the various timbers taken from the bedchamber were also sent off for tree ring dating, all the results showed that the trees had been felled in 1359 and 1360. Samples taken from the Great Hall, gave felling dates of 1425 and 1451, with another group dating from 1515, when it is thought the hall was extended.

14th Century records show that the house here in 1361, belonged to the Prior of St Oswald. It was called a hospicium and was originally a monastic hostel or town house. The ‘chief mansion’ in York, belonging to the Augustinian priory of St. Oswald at Nostell, near Wakefield in West Yorkshire. From the 12th Century the priors of Nostell had also been ‘canons prebendary’ of the Minster, meaning members of the cathedral’s governing body. So the prior would have used the house when visiting York.

The Priory of St. Oswald fell on hard times and the house in York was let (rented) in the 15th Century. At this time new building work was undertaken. At this time a larger and grander great hall was built, which included the fashionable canopied alcove for the high table.

Barley Hall was a prominent York townhouse by the 15th Century. Records from 1466 show the annual rent of fifty-three shillings and fourpence, a substantial rent that exceeded the entire annual wage of an average craftsman. At this time its tenant was William Snawsell. Snawell had adopted his fathers trade as a goldsmith and was a Freeman of York, meaning he could trade in his own right. In 1457 he had built himself a shop in a prominent trading position in York, just outside the cathedral gate. William’s wife Joan, was a relative of the Neville family, which helped him rise to the city’s Chamberlain in 1459 and eventually to become the Lord Mayor of York in 1468.

The tile pattern of the great hall was recreated to a pattern closely based on traces found on the original mortared floor, with references to surviving floors elsewhere. The interior has been furnished, as it would have looked in Alderman Snawsell’s time, in the late 15th Century. The furnishings have been created from new, in the fashion and style of their time.

Where possible, detailed copies of local items have been reproduced. Even the pottery has been copied from local finds. All medieval households would have a collection of pottery.

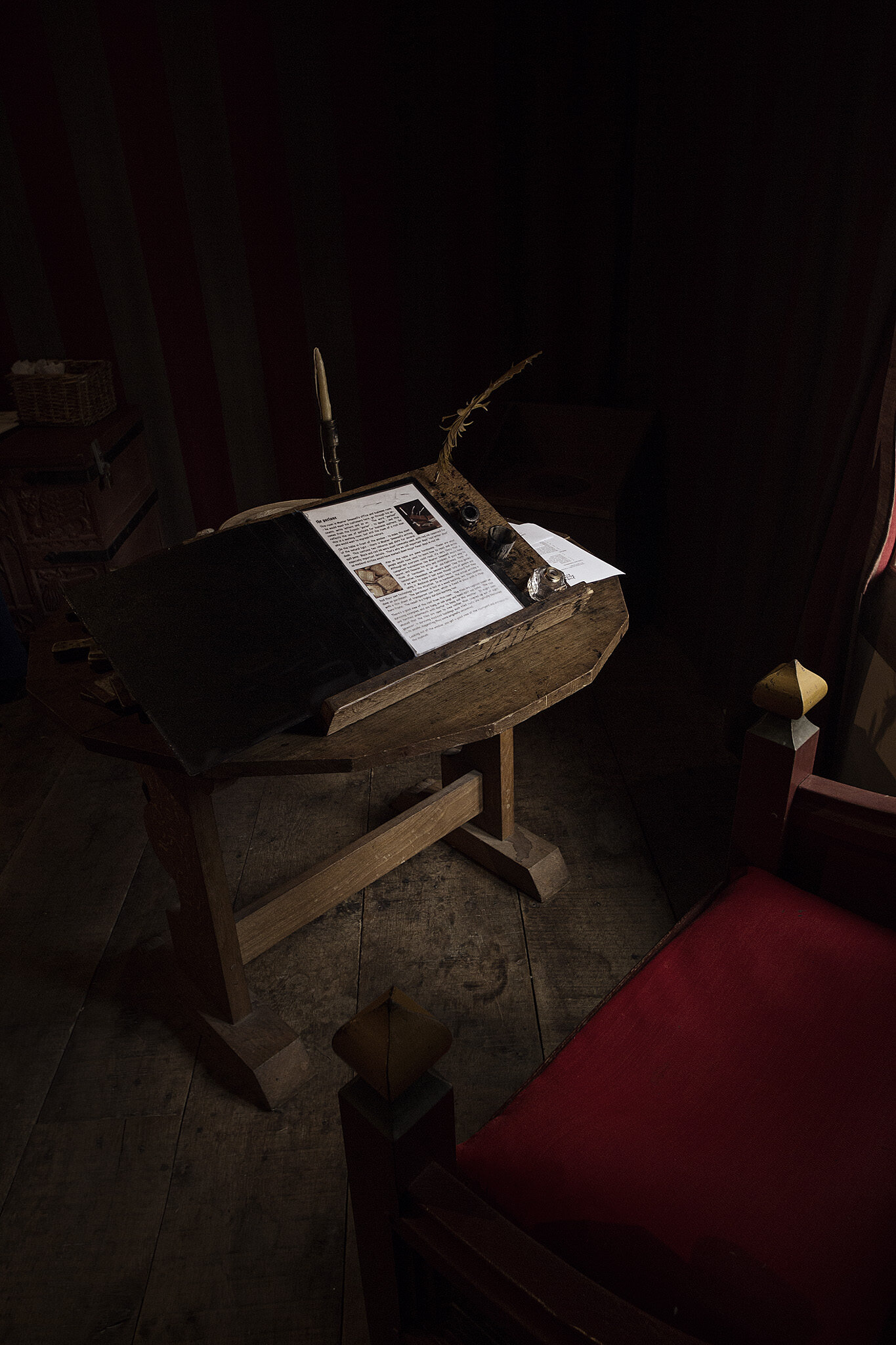

Glass was very expensive in medieval England. Often only the top of the windows would be glazed, even in large houses. The lower status rooms however, would still need windows and Barley Hall shows how this may have been done. It has a window which has been glazed with horn panels. The effect, while very difficult to see through, lets light in at a low cost. This may have been common practice in lower status homes. Horn was a versatile material, that was used for drinking vessels, inkhorns, spoons and horn books which were used to teach reading and writing, presumably because the ink could be washed off and the tablet reused.

All the fabric on the walls has been dyed from natural vegetable dyes. Some of the fabric has been painted. Painted cloths were also used in the middle ages, as they were far less expensive than tapestries.

Linen was used at meal times. The high table was furnished with fine linen, while the lower tables may have had lesser quality linen. Napkins were provided for mouths and fingers and placed over the shoulder. Laps where protected by a communal long towel, which would be draped across everyone’s laps. Meals in the middle ages were governed by complex etiquette and elaborate table manners. Many falsehoods have been portrayed that people ate with their hands, while in reality they would look down on how we eat today.

The buttery is where the wine barrels or butts were kept. The servant who worked in this room was the butler. The wine would have been for the Lord and his family only, while everyone else drank ale.

The restoration of Barley Hall has been a resounding success. It allows the visitor to go back in time and see what this type of home would have looked like in the 15th Century. It contains displays about daily life, what people would have had, and how things were made. It is not a traditional museum with ancient artefacts which can only be viewed, the building is instead about teaching, by allowing visitors to touch, use, handle and experience the building as a welcome guest.