Canterbury Cathedral, South East England

The earliest notion of a Cathedral at Canterbury is when King Ethelbert of Kent was baptized by St. Augustine. This was possibly done in an existing church, which may have been re-consecrated by St. Augustine in 602. Archbishop Cuthbert came along 150 years later and added a second building on to the existing church, which was intended to be both a baptistery and a burial place for subsequent Archbishops.

In 1011 Canterbury was under attack from Viking raiders, the city was burned and with it the existing church. The clergy, having taken refuge inside the church, were killed in the raid and only four members of the clergy escaped. Archbishop Aelfheah was captured by the Danes and taken prisoner for seven months, before being pelted to death with ox bones by angry Vikings, he was later Canonized.

After the Norman Conquest of 1066, the Cathedral at Canterbury was still in ruins. The newly created Archbishop Lanfranc, was invested at Canterbury in 1070, and the ceremony had to be held in an improvised shelter near the ruined church. It was his successor, Archbishop Anselm, under whose care the building of Canterbury’s crypt took place. Canterbury’s crypt is one of the largest in England, has changed little over the centuries, and in my option, is Canterbury’s most impressive feature.

The Cathedral above would be rebuilt and added to many times over the centuries, but the primary rebuilding and styling of the new Cathedral was at the end of the 12th Century, prompted by a fire, which had destroyed the choir. This important job was given to a master builder from France, named William of Sens. William was given the job of rebuilding the choir and completing the choir transepts. His resume consisted of the work he had done at Sens Cathedral, and in particular the new Gothic fashion which he was familiar with, which was never before used in England. William was working on the Cathedral when, in 1177, he fell from the scaffolding. Although he survived, he was badly injured and decided to return to France, dying there just three years later. His designs were carried out by the next Master Mason, William the English.

The crypt wall painting depicts the naming of St. John the Baptist, and is located in St. Gabriel’s Chapel in the Crypt at Canterbury. The painting dates from the 1130’s.

The Gothic style, which William of Sens brought to England, would become the dominant architectural fashion until the 16th Century. The defining Gothic arch, as it has become known, was an engineering innovation at the time that allowed for thinner walls and greater heights in buildings designs. As the style developed, features such as lantern towers, flying buttresses and rib vaulting further embellished the fashion. Gothic architecture is now roughly broken into three main categories, Early, Decorated and Perpendicular Gothic.

The Crypt at Canterbury Cathedral is one of the largest in England, and extends to about 290 feet in length. The oldest parts date from the late 11th Century. The newer part of the crypt has Gothic arches and was built by William the Englishman, who completed the work before his death in 1216.

The monks of the Benedictine Priory at Canterbury, also staffed its Cathedral. The Benedictine revival in England, during the 11th Century, was lead by Archbishop Dunstan, and Archbishop Lanfranc put his reforms into action. The organisation of the Cathedral became typical of most large medieval monastic houses in England.

The crypt was extended at the end of the 12th Century and a special watching chamber was created, so that the monks could watch the pilgrims who came to St Thomas’s shrine. The Chapel of Our Lady in the Cathedral’s crypt contains 14th century stone screens.

Intricately carved Romanesque capitals and columns can be found in the crypt at Canterbury, a capital being an architectural element, which divides a column from the masonry that it supports. These were often elaborately carved, and in the late 11th to mid-12th Century it was popular to decorate the capitals with animals, humans or symbolic figures. In the crypt at Canterbury, there is an abundance of dragons, demons and mythical creatures to be discovered.

What medieval Canterbury was famous for, was its shrine of Saint Thomas. It is impossible to tell the story of Canterbury without telling the story of Thomas Becket. Canterbury’s development and prosperity is inextricably linked to this 12th Century event which shocked Europe. Without the shrine of St. Thomas, and the vast number of pilgrims this brought to Canterbury for hundreds of years, the medieval city would not have evolved in the same way.

As with all stories, it is best to start in the beginning. Thomas Becket was born in London in 1118. His father was a merchant, who also held the office of Sheriff of London, and his mother, Matilda, was from Caen in Normandy. Thomas was bright and went to school at Merton Priory in Surry, where he was educated to become a clerk, having been taught grammar, logic, rhetoric and Latin. His learning would have opened two paths to him, he could choose to become a member of the church, or work for the nobility. He continued his studies in Paris, which was then the best school in Europe. After studying for a further 5 years in Paris, he returned to England in 1140 and took up a position with Theobald, Archbishop of Canterbury. As part of this position, he was sent to further study Canon and Civil Law, in Bologna and Auxerre.

When King Stephen died in 1154, his nephew, Henry of Anjou, became Henry II of England. It was Archbishop Theobald who recommended Thomas Becket to King Henry, and Henry installed Thomas as Chancellor of England. The two men got along well, and their mutual respect seems to have been based on certain traits they had in common, both men were well educated, determined and decisive. Thomas Becket excelled in his role as friend and Chancellor to the King.

It may have seemed only logical to King Henry II, that when the Archbishop of Canterbury died in 1161, to offer the post to his friend Thomas Becket, who had always worked towards the Kings interests. The minor problem, that Thomas was only a clerk who had taken minor orders, was soon rectified and he was ordained a priest on the 2nd of June 1162. The following day, Thomas Becket was consecrated as Bishop in the morning, and then enthroned as Archbishop of Canterbury in the afternoon. Almost certainly, they wanted to get the job done before too many people could complain. The reason this was important to King Henry was because of the political unrest between church and state. There was at this time one law for members of the church, and another for laymen.

We don’t know exactly what Thomas Becket thought of his new appointment. Was it was a role that he ambitiously took, or one which was thrust upon him by the king? Either way, it wasn’t long before the happy friendship between the King and the Archbishop was frayed. Thomas Becket was a man who took his job seriously, and did it well. When that job was Chancellor of England and reporting to the King, he excelled at the King's wishes. Once the job was leader of the Catholic Church in England and answerable to God, above the King, he did it equally well. However, this left King Henry II outraged that his friend, and the man he had raised to his station, would defy him. King Henry however had a good point - as the medieval King who had done more for law and order than almost any other, he felt it unfair that members of the church did not abide by the common laws of England, but instead were tried in church courts, often leading to much lighter sentences for their crimes. This was not just for monks and priests but also for any clerk, who took even minor orders, and committed secular crimes. Henry felt that this deprived him of the ability to govern effectively, and undercut the laws of England. This he wanted to abolish, as King Henry saw this as an obstacle to improving the legal system. It was under Henry II that that the jury system was created.

In 1164, King Henry II wrote the Constitutions of Clarendon, which was a series of clauses that clarified the relationship of the church and the state, and asserting the judicial rights of the Crown. Thomas Becket at first agreed to the document, and then later withdrew his consent, which infuriated Henry. The rift between the King and the Archbishop came to a boiling point when Thomas Becket was summoned by the King, to meet in Northampton. King Henry called the Archbishop to account for the money had spent while Chancellor, which angered Thomas, and arguments ensured during which the Bishop of London tried to wrench Thomas’s Primatial Cross from his hands, and the Archbishop compared himself to a martyr and fled to France in October of 1164. He remained in exile for 6 years, first at the Abbey of Pontigny, and then at Sens.

While Archbishop Thomas Becket was in exile, King Henry II decided to crown his own son, Henry, the Young King in his Lifetime, something practised by the French Capetian Kings to create a smooth succession, and considering the trouble Henry II went through to claim his throne, it made sense that he would take this step. The crowning of a King was the job of the Archbishop of Canterbury, but King Henry II asked the Archbishop of York to carry out the coronation, further upsetting Becket in exile, who threatened excommunications and interdicts. In his six years in France, he never gave up his title or the power of his office, and in 1170, while King Henry II was in Normandy, Becket travelled back to England, landing in Sandwich and was greeted by cheering crowds.

It was the Archbishop of York that is said to have sparked the Kings temper, while in an audience with King Henry II at Bures in Normandy, where he is thought to have stated to the King that ‘While Thomas lives, you will have neither quiet times nor a tranquil kingdom.’ The King then flew into a rage and uttered the fateful words, ‘Will no one rid me of this turbulent priest’. Four knights, overhearing the King, quietly set off for Canterbury.

The King’s Knights, Richard Brito, Hugh de Moreville, Reginald Fitz Urse, and William de Tracy, took King Henry II at his word, and made their way to confront the Archbishop of Canterbury. They arrived at Canterbury on the 29th of December, 1170. They requested an interview with the Archbishop Thomas Becket, where further arguments ensued and when the cries of ‘Kings Men’ were heard, the monks pleaded with the Archbishop to enter the Cathedral, fearing for his safety. Becket entered the Cathedral but insisted that the door be left unbarred. The Archbishop made his way through the north-west transept, during the afternoon service of Vespers. The Knights entered the Cathedral, and called out to the Archbishop, who came to face them.

The story of Thomas Becket may be best told by an eye witness, a monk named Edward Grim, who was visiting Canterbury Cathedral and was with Thomas Becket on the 29th of December, 1170. He published his account 10 years later, which reads:

‘With rapid motion they laid sacrilegious hands on him, handling and dragging him roughly outside of the walls of the church so that there they would slay him or carry him from there as a prisoner, as they later confessed. But when it was not possible to easily move him from the column, he bravely pushed one [of the knights] who was pursuing and drawing near to him; he called him a panderer saying, "Don't touch me, Rainaldus, you who owes me faith and obedience, you who foolishly follow your accomplices." On account of the rebuff the knight was suddenly set on fire with a terrible rage and, wielding a sword against the sacred crown said, "I don't owe faith or obedience to you that is in opposition to the fealty I owe my lord king." The invincible martyr - seeing that the hour which would bring the end to his miserable mortal life was at hand and already promised by God to be the next to receive the crown of immortality - with his neck bent as if he were in prayer and with his joined hands elevated above - commended himself and the cause of the Church to God, St. Mary, and the blessed martyr St. Denis. He had barely finished speaking when the impious knight, fearing that [Thomas] would be saved by the people and escape alive, suddenly set upon him and, shaving off the summit of his crown which the sacred chrism consecrated to God, he wounded the sacrificial lamb of God in the head; the lower arm of the writer was cut by the same blow. Indeed [the writer] stood firmly with the holy archbishop, holding him in his arms - while all the clerics and monks fled - until the one he had raised in opposition to the blow was severed. Then, with another blow received on the head, he remained firm. But with the third the stricken martyr bent his knees and elbows, offering himself as a living sacrifice, saying in a low voice, "For the name of Jesus and the protection of the church I am ready to embrace death." But the third knight inflicted a grave wound on the fallen one; with this blow he shattered the sword on the stone and his crown, which was large, separated from his head so that the blood turned white from the brain yet no less did the brain turn red from the blood; it purpled the appearance of the church with the colors of the lily and the rose, the colors of the Virgin and Mother and the life and death of the confessor and martyr. The fourth knight drove away those who were gathering so that the others could finish the murder more freely and boldly. The fifth - not a knight but a cleric who entered with the knights - so that a fifth blow might not be spared him who had imitated Christ in other things, placed his foot on the neck of the holy priest and precious martyr and (it is horrible to say) scattered the brains with the blood across the floor, exclaiming to the rest, "We can leave this place, knights, he will not get up again.’

The exactly location of Becket’s murder has been preserved, in the north-west transept, under a sword. Within hours of Becket’s death, the Cathedral was full of mourners. His body was placed in an iron chest and laid within a wooden coffin. Two days later, it should be no surprise that miracles began to occur. This warranted his Canonization only three years later.

King Henry II did not celebrate the death of Thomas Becket, in fact he did just the opposite, either because it prudent for him to do so, or because he never actually intended for his words to be taken seriously. On hearing of the death of his old friend and enemy, Henry locked himself in his chamber for three days and refused food or any social interaction. He was certainly concerned that he would be excommunicated, and he begged forgiveness and reconciliation from the Pope. He also agreed to abrogate the Statutes of Clarendon, and restore the Church of Canterbury to all its rights and possessions. He offered to go on a three year crusade if the Pope wished him to, and to support two hundred knights in the Holy Land, with these promises Henry was forgiven.

Where historians think the truth can be found, is in Henry’s actions two years later when, on the 12th of July 1174, King Henry II chose to make a pilgrimage to Becket’s Tomb at Canterbury. He dismounted from his horse as he came into sight of Cathedral, and walked as a penitent pilgrim, barefoot, through the streets. He knelt in the porch of the Cathedral and kissed the sacred stone on which the Archbishop had been murdered. He wept before the crypt and spoke of his remorse at uttering those fateful words. King Henry also asked the Prior, and all 80 monks, to flagellate him with a scrounge, similar to a multi-tailed whip, over the tomb of St. Thomas, in order to free him of his sin. No other medieval King ever undertook this humiliating act, and while it is safe to say that King Henry II must have had a complicated relationship with Becket, in these acts we can see genuine grief.

The unique Romanesque staircase in Green Court dates from 1153 and leads to the North Hall where pilgrims were once given lodging just inside the Cathedrals gates.

Prior Wilbert was assigned to his post at Canterbury in 1153, a post which he held for 14 years. During this time he created a water supply for the monastery, which included an aqueduct made with pools, washbasins and bowls that were filled from the springs north east of the Cathedral. The water was taken to a conduit house, through the city wall and through to the canons of St Gregory’s Priory, who appreciated the gesture and gave a yearly basket of apples in return for their use of the water.

Prior Wilbert also created a water tower, where the water was sent up brass pipes to a cistern on the first story, so that the monks could wash. Prior Wilbert also devised a system for flushing the drains, using rainwater from the gutters on the Cathedral's roof. His 12th Century water tower still stands today.

The eldest son of Edward III, was Edward of Woodstock, who has come down in history to us as the Black Prince. He broke with custom when choosing a wife and married his third cousin, Joan of Kent. This required a dispensation, which was granted from Pope Innocent VI. Part of this agreement was the Edward would found a chantry chapel at Canterbury Cathedral. The chantry would have two altars, with a priest for each. There have been many explanations as to why he was called the Black Prince; the answer is we do not really know. It is unlikely that the Victorian theory, that he wore black armour, is correct. It is more likely that as a warrior prince he instilled fear in his enemies, but there is just not enough evidence for certainty, only speculation.

Edward, the Black Prince, spent most of his life campaigning and leading armies against the French, with great successes at Crecy and Poitiers. Towards the end of his life he suffered from dysentery and other afflictions, which a life in battle can bring. Although we don’t know exactly what he died from, it is safe to assume that the years of war took their toll. His eldest son, Edward, died just before his return to England in 1371, where he met his father King Edward III at Windsor, before heading to his manor at Berkhamsted to recover.

In 1376, Edward, the Black Prince, was again unwell and it wasn’t long before he was aware that he was dying. He had severe dysentery and often fainted from weakness. He died at the Palace of Westminster and was buried at Canterbury Cathedral on the 29th of September 1376. While he had requested to be buried in the crypt, it was felt that this was not suitable and that he should have a more prominent place in the Cathedral. His tomb lies on the south side of Trinity Chapel, next to where Becket’s shrine once stood. Above the effigy hangs a painted tester and over this are replicas of the surcoat, helmet and gauntlets that belonged to the prince, the originals are inside a case nearby. His epitaph inscribed around his effigy reads:

Such as thou art, sometime was I.

Such as I am, such shalt thou be.

I thought little on th’our of Death so long as I enjoyed breath.

On earth I had great riches, land, houses, great treasure, horses, money and gold.

But now a wretched captive am I, deep in the ground, lo here I lie.

My beauty great, is all quite gone, my flesh is wasted to the bone.

In 1377, only a year after the death of Edward the Black Prince, King Edward III also died. This meant that the heir to the throne of England was the Black Prince’s son, the 10-year-old Richard II. His uncles, John of Gaunt and Thomas of Woodstock, lead the regency councils and this went surprisingly well for a time. It wasn’t until after the death of John of Gaunt, in 1399, when things started to really unravel. Richard II had disinherited Gaunt’s son and his own cousin, Henry of Bolingbroke, who was already living in exile, having previously rebelled against the king in 1387. Henry of Bolingbroke returned to England under the pretence of reclaiming his inheritance, but his army grew and he deposed King Richard II and had himself crowned King Henry IV. Richard II died while in captivity; it is uncertain exactly how he died.

Although Henry IV took the throne from his cousin Richard II, it did not mean he was next in line to it. In fact, there were two other Princes who came first. They were Edmund and Roger Mortimer, who were just children at the time their cousin declared himself Henry IV, but they were closer in line to the throne being descended from Lionel, Duke of Clarence, who was the second surviving son of Edward III, whereas Henry IV was descended from Edward III’s third son, John of Gaunt. Therefore, Edmund Mortimer, under the laws of primogeniture, was Heir Presumptive. The fact that this didn’t happen, that we don’t have a Kind Edmund, is the foundation of what caused the Wars of the Roses. However, unlike the Wars of the Roses, there was no thought that these Princes, Edmund and Roger, were not being treated well. They were looked after in the King's household. Even though they were used in a treasonous plot in 1405 and abducted, they were not implicated, and from then on lived in the Prince of Wales' (later Henry V’s) household.

Henry IV’s reign was not peaceful, and there were numerous plots to overthrow him. We know that he had some form of skin disease, which disfigured him, often thought to have been leprosy. In the last five years of his life, he suffered from an acute illness on at least six occasions. He died at Westminster, on the 20th of March 1413. His second wife, Queen Joan, died in 1437 and they are both buried in Canterbury Cathedral, across from his uncle, Edward, The Black prince, who was the father of the King he deposed. They are portrayed in an alabaster carved effigy, under a canopy that is painted with their royal arms.

The priory of Christ Church was re-established alongside the cathedral by Archbishop Dunstan in the 10th century. It is one of the largest and best documented of Britain’s Benedictine monasteries. The buildings that survive today, other than the Cathedral itself, were built primarily between 1077 and 1540. A visit to the Cathedral should not leave out the surrounding area. The Cathedral itself sits within a walled precinct, with many historic buildings clustered around it, many of which date from its time as a priory.

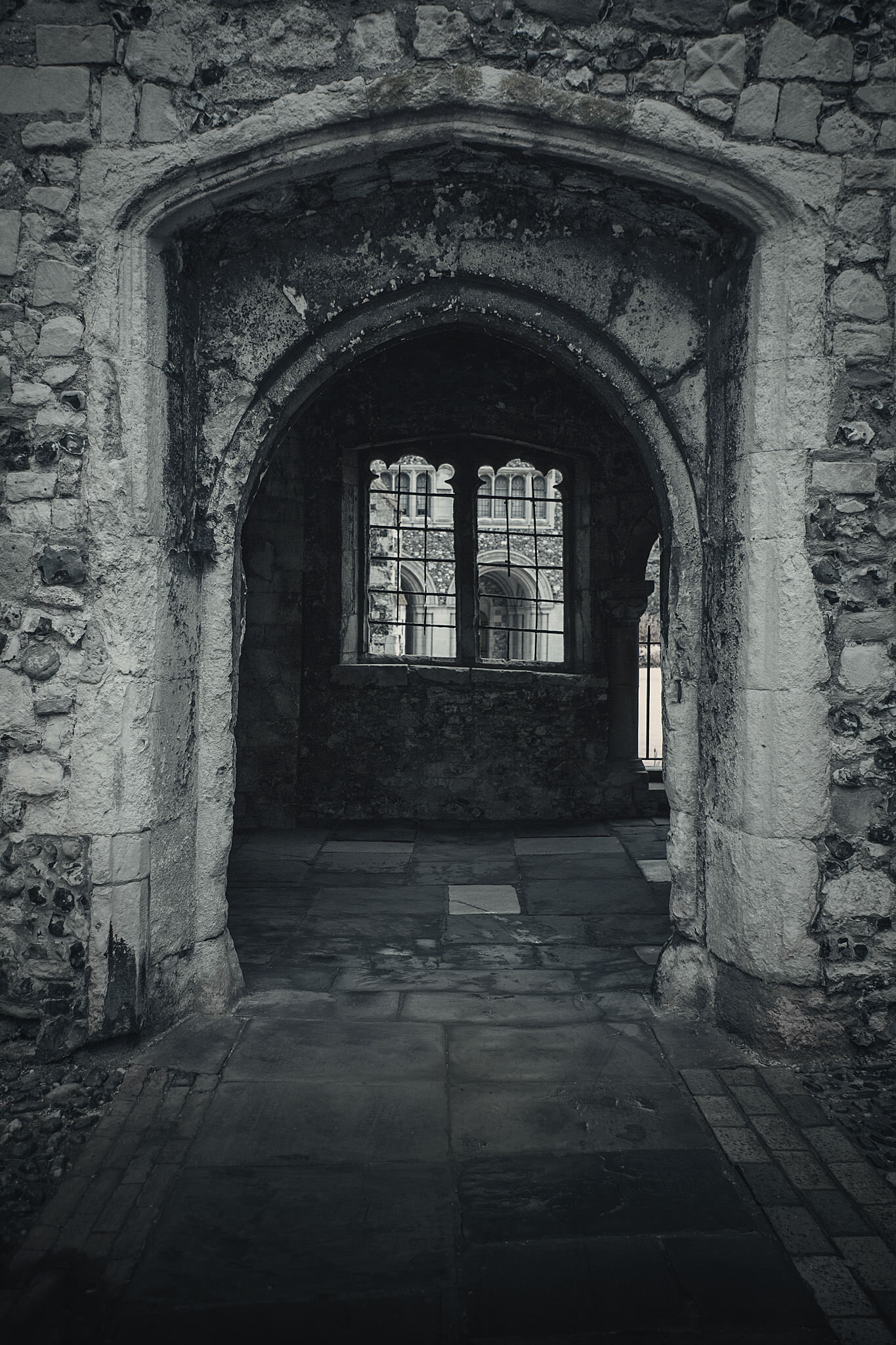

The passageway that joins Green Court to the Cathedral, has become known as Dark Entry, possibly because of the lack of light inside it. This originally connected the Prior’s Lodgings and the school, to the Cathedral and cloisters. It was built in the late 14th Century.

On the 21st of May 1382, Canterbury Cathedral was hit by an earthquake, in which the cloister and chapter house were severely damaged. The old nave was already undergoing rebuilding work, and in the 1390’s, a great deal of construction was in progress. When Archbishop Courtenry died in 1396, he gave £200 to the rebuilding of the south walk of the cloister. This was the section closest to the nave, that would lead from the Archbishop’s Palace to the Martyrdom, the route that Thomas Becket took on his final journey before his murder. The work ultimately cost £300.

The Great Cloister was completed in the early 15th Century and is an outstanding example of Perpendicular Gothic work. It was rebuilt over the walls of Lanfranc’s original Norman cloister.

Parts of the old 12th Century infirmary cloister have also survived. This is part of the network of passages which today lead from Green Court to the Cathedral. This smaller, infirmary cloister, separated the sick and infirm monks from the healthier and active members of the community.

Archbishop Winchelsey wrote in 1298:

‘All doors to remain closed that lead from the Palace towards the Cloister, except those from the Cellerarium which must necessarily remain open but must be carefully guarded against the entrance of women.’

The doorway from the cloister into the Cathedral, it is thought that it was used by the four Knights who came to murder Archbishop Thomas Becket. The doorway was also somewhat embellished during the cloisters rebuilding, in the early 15th Century.

Like all monastic communities, the Benedictine Priory that was part of Canterbury Cathedral was suppressed under Henry VIII and its formal surrender came in 1540. On the 53 monks who lived and worked there, twenty-eight became members of the new Cathedral Foundation and the others were pensioned off.

At the time of the Dissolution of the Monasteries, the Priory at Canterbury was the third richest ecclesiastical house in Britain, with the first being the Abbey at Westminster and the second being Glastonbury. The first suppression of the smaller monasteries, was implemented on any monastic community which earned less than £200 annually, the Priory at Canterbury was earning nearly £3,000. Christchurch Priory had the most lucrative shrine in the whole of England, that of St. Thomas Becket, which brought in huge amounts of money.

After the Dissolution, Henry VIII set up a ‘New Foundation’ at Canterbury for the Dean and twelve canons, minor canons and six preachers, with lay clerks, porters and masters of pupils of the school. Many of the Priory’s buildings were adapted for the houses of the new officials. Because of this, many of the Priory’s buildings have survived in some form.

What is now known as, The King’s School, in Canterbury, was renamed and re-established by Henry VIII, in 1541. It is, possibly, the oldest school in Britain, having been established by St. Augustine in the 6th Century, although nothing remains from this early time.