Chester, North West England

Chester is thought to have been founded by the Romans, although archaeology suggests that it may have also had earlier occupation. The Romans however, founded the city of Chester as Deva around 75 AD. It is thought they took the name either from the River Dee, or the Goddess of the Dee. Chester’s Roman Amphitheatre dates from the 1st Century and has been partially excavated, today it is in the care of English Heritage. The Roman town of Deva was a prosperous trade centre with its access to the river. It also contained a fortress and bathhouse, all of which were abandoned by 410AD.

After the Romans departed Chester, the Anglo-Saxons resettled the town. Early in the 10th Century, Aethelflaeda, the daughter of Alfred the Great, established Chester as a defended settlement and refortified its Roman walls. Part of the city walls still remain today, although expanded and rebuilt as needed though the centuries, part of these walls are still Roman and Saxon.

By the time of the Norman Conquest of England, in 1066, Chester was a wealthy and prospering town. It also contained a mint which employed 20 moneyers. Much of the city’s important trade had been with Dublin, which at this time was a Viking town. Dublin was exporting furs, hides and fish to Chester. After William the Conquerors arrival, he built Chester Castle and established the Earldom of Chester, which he gave to his nephew Hugh d’Avranche, also known as ‘Lupus’ meaning ‘the Wolf’. At this time, the population of Chester is estimated to have been between 1,500 and 3,000, depending on the source.

In 1245, King Henry III rebuilt Chester Castle in stone. In the 18th Century, the castle was used as a prison but only part of it survives today as the site has, in part, been built on and newer buildings now occupy what was once the medieval castle. Although there were troubled relations between the English and the Welsh at this time, the people of Chester were encouraged to trade with the Welsh. The Welsh however, were not given equal status with the English and the French, as can be noted when reading court documents, where they were given less generous treatment.

In 1309, cooks in Chester were fined for scorching the street surface outside the Buttershops. Cooks were allowed to set up their hearths in the street, but they were expected to take care while cooking and watch their fires. A number of fires had gotten out control and damaged the ‘common soil’ of the city. The authorities fined the street cooks, but the residents of the Buttershops were not happy and are said to have described them as a ‘flaming nuisance’.

In 1484, the citizens of Chester claimed that the city was wholly destroyed, because of the silting of the harbour. The city had been in decline since the mid-15th Century. Access to the harbour had been declining since the 13th Century. The citizens also reported that Welsh traders avoided the town because of the high tolls. By the 16th Century, the city was once again prospering and new buildings were being erected. At this point the city had strong agricultural interests, and arable land was rented. Livestock became the mainstay of the local economy. Chester’s market was protected in law, with no other market allowed within 4 leagues (12 miles).

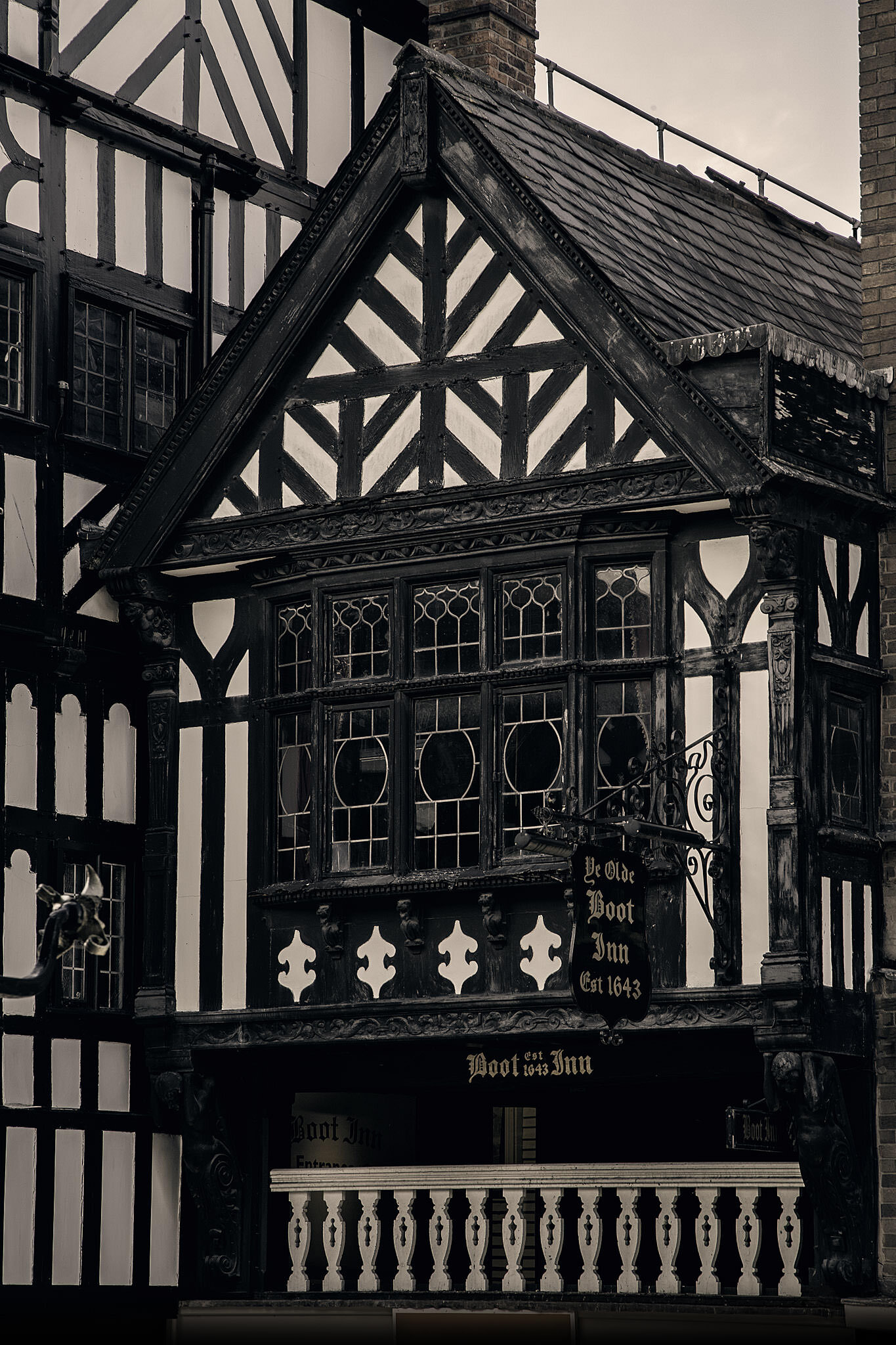

The Rows in Chester, are a series of two tiered and primarily half-timbered, shopping arcades in the centre of the town. The Rows take their name from the traders who carried out business here, so there would have originally been Shoemakers Row, Ironmongers Row, Mercers Row, where you would find textile deals, and Lorimers Row, where you could buy a new harness for your horse. There was also a Welsh Row, where Welsh goods were sold. In the Middle Ages, the shopkeeper would have lived on the premises. Most of these are built on sandstone bedrock, and as a cellar was needed, the geology of the area meant that the buildings needed to be higher than other towns.

In the 16th Century, the shops were expanded outwards originally, with jetting supported on posts set into the street. In time, more shops filled the spaces at street level, and over the centuries the gaps between the houses were built up and the galleries joined together. Some of these galleries, or balconies, would also have sloping outer boards which were used for displaying wares.

The iron work clock now sits on the site of what was once the Roman entrance to the town. The clock was conceived originally to celebrate Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubliee, but it was late, and it took two more years than anticipated to complete it. There is no doubt that Chester is a beautiful town, full of history, but today there is also much that visitors need to look past. Many of the building are in need of work and pigeons have taken up residence in many of the balcony’s and rooftops of the Rows. The ground floor of all of these buildings now has modern shops, whose advertisements are in sharp contrast to the old architecture.