Hampton Court, Greater London

I am pushing the time period here with Hampton Court; it is not a medieval building. However it may be the most important Tudor Palace that remains in existence and therefore it is worth including as there is much we can learn about the late medieval court from it.

The first buildings to be built at Hampton Court belonged to the Knights Templar. The Templars acquired the manor of Hampton in 1236 and used the site as a grange, or farmstead. Excavations suggest that there was a great barn here and a stone room that may be been used as an office for the estate.

The land was given to the Knights Hospitaller, like many other Templar holdings, after the Knights Templar order was disbanded. In the 15th Century it was used by the Abbot as a rural retreat and some new residential buildings were added. Henry VII and his wife Elizabeth of York visited Hampton in 1503.

In 1514, the property was given to Thomas Wolsey, Archbishop of York and chief minister to the young King Henry VIII. In 1515, Wolsey was appointed Cardinal and Lord Chancellor of England. Soon afterwards the rebuilding of Hampton was started. Wolsey did not forget the King in his architectural plans and made provision for a set of lodgings for Henry VIII, his Queen Catherine and their daughter Princess Mary. These were later demolished.

Thomas Wolsey was once the most powerful man in England. His fatal mistake was that he did not manage to obtain consent from the Pope for Henry’s divorce from his first wife, Catherine of Aragon. For this error and because he had built a palace fit for a King at Hampton he was forced to relinquish Hampton Court to the king.

Within six months of Henry VIII obtaining Hampton Court, he had begun building work. Over the next 10 years Henry spent over £62,000 on improvements at Hampton Court, a sum worth nearly £20 million today.

Although Hampton Court remained a Royal Palace and underwent many changes, it was always the serving rooms in large houses that were the last to be improved. Luckily this meant that the Tudor kitchens have survived virtually unaltered. The kitchen buildings began to be built by Cardinal Wolsey in the early 16th Century. However when Henry VIII took over the palace, they were extended to be able to contend with his household of 1,200 people.

The kitchens were divided into 15 separate offices with sub-departments. These included the spicery, which stored spices, the confectory for sweets and pastries, the pastry, which made pastry cases and crusts. Each of the departments were then allotted rooms around the kitchen courtyards.

The serving place was where dishes were dressed and garnished, before being sent upstairs to waiting courtiers. This is where, for example, if you were serving peacock, the uncooked skin and feathers would be placed back over the cooked meat, so that the animal would look as lifelike as possible when being served. The serving of the dishes was a great display.

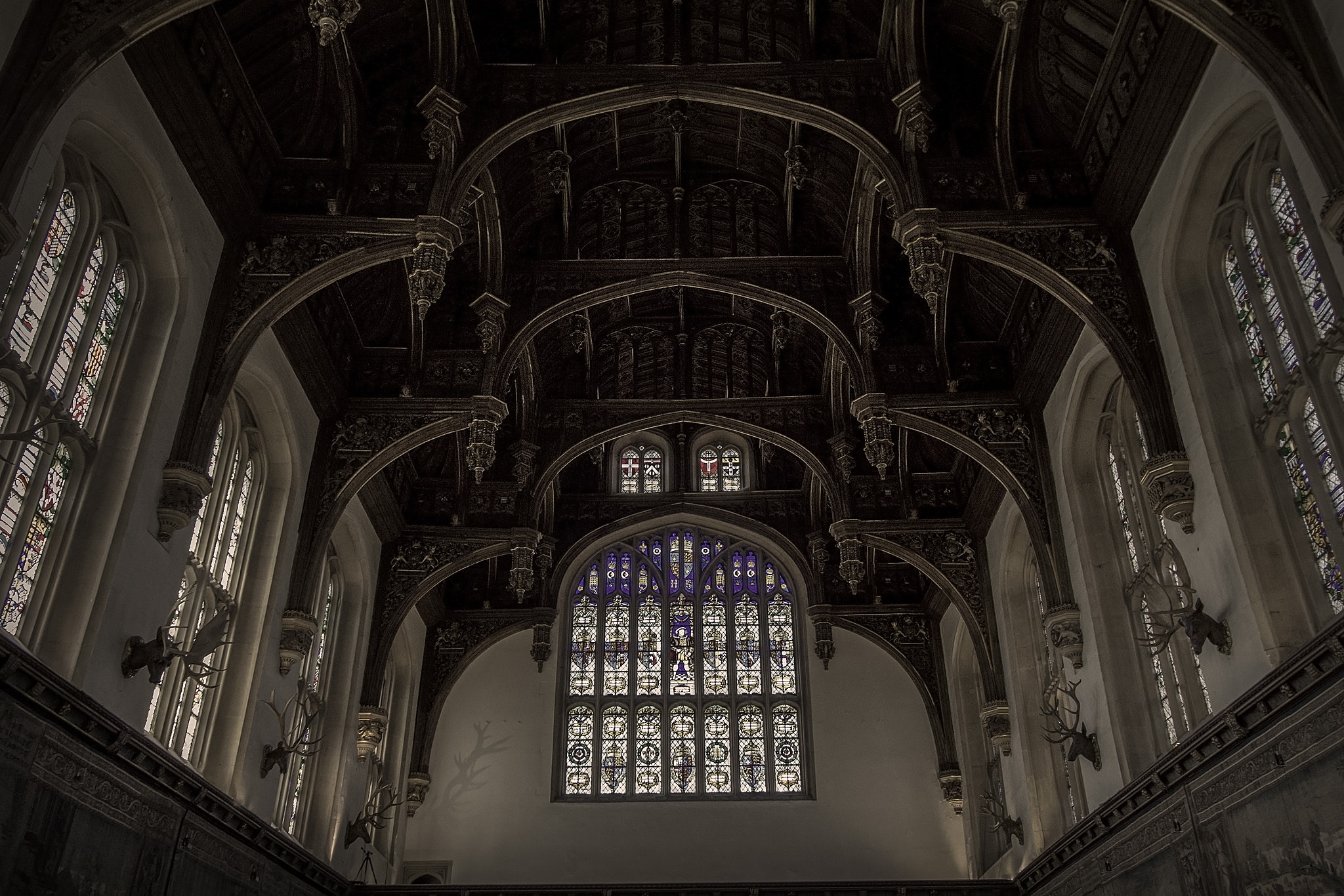

The great hall at Hampton Court was re-built by Henry VIII to replace a smaller and older hall. It is 32 meters (106 feet) long and 12 meters (40 feet) wide. A hammer-beam roof was used to cover the width span because it could use cantilevered beams, projecting from the wall and supporting elaborately braced trusses. The roof was designed by the King’s master carpenter, James Nedeham and is richly decorated with pendants, badges painted carvings and royal arms. Originally the entire ceiling would have been painted with blue, red and gold.

From the time it was built, Hampton Court like most wealthy houses in London would have been approached by water.

All of Henry’s six wives visited Hampton Court. New lodgings were built for most of them. The King also had his own rooms rebuilt several times. Accommodation was also built for each of the King’s children and a large number for visitors, courtiers and servants. By the time Hampton Court was finished in 1540, it was one of the most modern, and magnificent palaces in England.

Hampton Court also had were tennis courts, bowling alleys and pleasure gardens for recreation, as well as a hunting park of more than 1,000 acres. It had a large communal garderobe or lavatory known as ‘The Great House of Easement’ which could seat 28 people at a time. This was for men and boys and was positioned over the moat. Its discharge flowed out into the Thames where a lock prevented it from re-entering the moat.

When Henry VII died in 1547, he owned more than 60 houses and Hampton Court was one of his favourites.

The Royal Court comprised those who were with the Monarch at any particular time and a strict etiquette and hierarchy was always used. At the top of this pyramid was of course the king. The next highest offices were those of The Lord Chamberlain, who would direct public ceremony and The Master of the Horse, who would be in charge of the kings transport, hunting and the royal stables. There was also the Lord Steward, who was the head of all the domestic arrangements, The Dean of the Chapel Royal, who was responsible for all the clergy and both the public and private chapels, and The Groom of the Stool, who was the head of the King’s own private servants. The name came from one of his duties, namely attending to the King while he was on the lavatory or stool. All of these offices had many servants under them, sometimes up to 600 positions for each department, all of which would be moved around with the King as he traveled.

Henry VIII’s one and only legitimate son Edward VI, was born at Hampton Court in 1547 and he was Christened in the royal chapel there. His mother Jane Seymour, died at Hampton Court just days after his birth. Henry, years after her death, created his fantasy family portrait which still hangs at Hampton Court, where he is shown with his son Edward, now around 7 years of age and his wife Jane, in the wings are his daughters Mary and Elizabeth. This painting says a lot about Henry, he wanted a painting of what never was, and lets not miss the codpiece.

The King’s apartments at Hampton Court were built for William III at the end of the 17th century. Henry VIII's apartments were destroyed during the remodeling work carried out by William and Mary. They had commissioned Christopher Wren to completely rebuild Hampton Court. It was originally planned to demolish the entire palace and rebuilt it completely, with the exception of the great hall. The project ran low on funds and so, thankfully, was not completed.