Holywell, North Wales

Medieval thought seems to be alive and well in the town of Holywell to this day. Reality seems subjective here, and we are asked to suspend our knowledge of what the word ‘fact' actually means when reading the explanation of Holywell written by the Holywell and District Society, and the Holywell Churches websites, which both boldly state:

“The town of Holywell takes its name from the fact that in c650 a young and beautiful maiden by the name of Winefride was walking in the valley, when she was approached by a group of men, led by Prince Caradog from Hawarden. The Prince attempted to seduce Winefride but was refuted, at which he drew his sword and struck Winefride’s head from her body. The legend states that her uncle Saint Beuno was called and he replaced her head and she was restored to life. The place where her head had fallen erupted into a great spring, thus the holy well.”

While this is the general story, versions vary a little, reality hasn’t escaped everyone in Holywell, and there are plenty of people who will tell you about the story or legend of Saint Winifred. Surely we can call it a story or a legend and not talk about it as being a ‘fact' today.

So let us approach this story from reality, in which case we can appreciate the story and legend of St. Winefride. Holywell itself can attribute its existence today to the legend of St. Winefride, which has caused a vast number of pilgrims to travel to this small town, so we can see why it is in their interests to continue to believe in the legend. However, surely it is just as interesting to study the legend and the human behaviours which this story created. The legend of St. Winefride has seen pilgrims travel to Holywell for possibly over 1,000 years. Although we really don’t know for exactly how long this occurred.

So who was St. Winefride and what is the story? Firstly, we know her as Winefride, the English version of her name, in Welsh she is Gwenfrewy. The legend would have us believe that she was the daughter of a local Welsh prince named Tewyth, and she was also the niece of St. Bruno. In the year 630, a local chieftain named Caradoc from Hawarden, attempted to have his way with her. She however, ran from him, and headed toward the church thinking to escape. Caradoc pursued her, and in doing so cut off her head, and miraculously upon the place where her head landed, a spring of water appeared. St Bruno then came out of the church, picked up her head and placed it back on her body. He prayed over the body and her head reattached itself and she came back to life, although Winefride was left with a white scar on her neck. Caradoc sank to the ground and vanished after the event, while Winefride became a nun and joined the monastery at Gwtherin, where she later became the Abbess. Some stories give more details, others alter the details a bit, but other all this is the story. Obviously, the resurrection of Winefride could not possibly have happened like this, but the legend may have some facts in it. Winefride may have been related to the house of Powys, and her uncle or her brother may have killed Caradoc in an act of vengeance.

The well itself was believed to have healing properties. This is not just mystical, there is actually some truth to this, or rather there was some truth to it. In the 1880’s, the well dried up due to mining on the Halkyn Mountain, but of course the town needed the well, or rather it needed the money the well brought in, and so the water began to be piped in instead, from a different water source in 1917. The original water would have had a high concentration of minerals some of which are known to help the body. The water temperature in the old well was said to be 50 degrees. There are still places in Europe where doctors will prescribe that patients 'take the waters' to this day, and this was also very popular in the 18th and 19th Centuries. This is probably where the legends come from that the water had healing properties, it is the element of truth in what is a great story.

Some of the people who set out on a pilgrimage to Holywell in the Middle Ages, were royal visitors. The first of these was King Richard I, who visited in 1189. Henry V visited in 1416, where he went on foot, from Shrewsbury Abbey to Holywell, as an act of reverence. King Edward IV visited in 1461, where an account tells us that he took a handful of earth and placed it upon his crown. James II and Queen Mary Beatrice visited in 1686, where the priest at the time gave the King a chemise which had been worn by his great grandmother, Mary Queen of Scots, supposedly to her execution. In 1828, King Leopold of Belgium brought his niece, the future Queen Victoria, to Holywell.

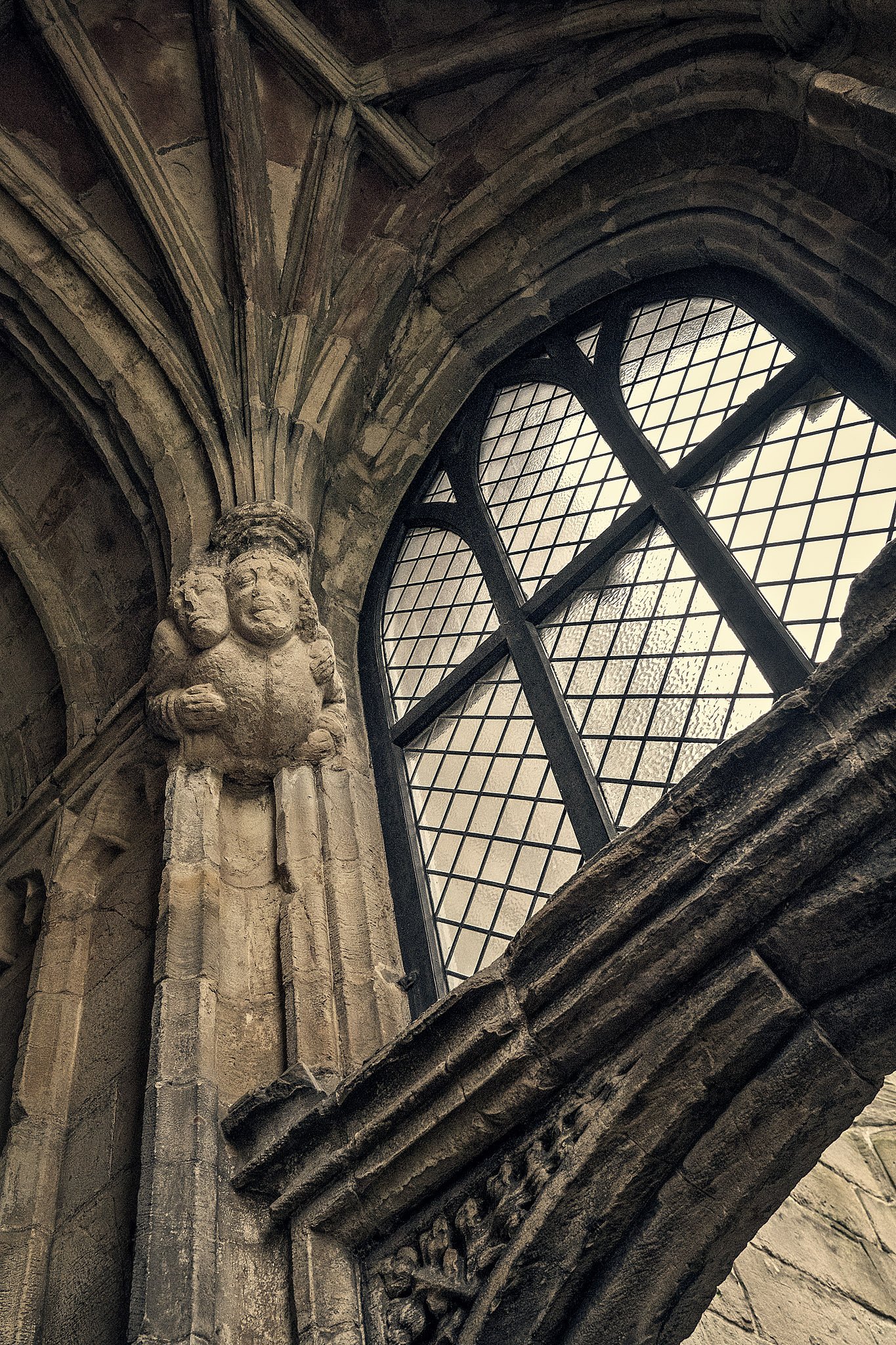

The building we see today, over the well, was built at the turn of the 16th Century. Funds were given by Margaret Beaufort, the mother of Henry VII, for its creation, with contributions being also made by other noble families. The structure is built in the perpendicular gothic style. The spring itself forms a basin, which is enclosed by octagonal stonework. The shrine itself was a point of contention between Basingwerk Abbey and St. Werburgh’s Abbey, both of which fought for control of the shrine.

Eight stone columns rise from the basin which meet overhead in a tracery canopy. Above this is the chapel of St. Winefride, where pilgrims would spend the night in prayer before bathing in the waters. There are still times where bathing is allowed here, although not in the oldest parts. St Winefride remained popular throughout the Middle Ages. William Caxton published a 16 leaf folio entitled ‘The lye of the blessed vyrgyn saint Wenefryde’, at the end of the 15th Century.

When the legend of St. Winefride was first created, is also a mystery. The first record of the place name of Holywell doesn’t appear until 1093, in the gifting of the ‘church of Haliwel to St. Werburgh’s Abbey in Chester’, by the wife of the Earl of Chester. So for the 400 years before this, we have no information on the well at all, although the settlement known as ‘Haliwel’ was mentioned in 1093, which suggests that the village had become known for the story of St. Winefride. It is also curious that Giraldus Cambrensis, who stayed the the nearby Basingwerk Abbey in 1188, in the company of Archbishop Baldwin of Canterbury, makes no mention of Holywell in his writings.

There were once many natural wells, or springs, in England and Wales. They were commonplace, and like other commonplace and important things in the pagan world, the church wanted to incorporate them, and in doing so give them new meaning. So the early church bound them into a belief system which was acceptable to itself. Many of these waters have been long lost or forgotten, many that do survive are near churches, which suggests a dual location of importance. In its medieval day, St. Winefride’s well at Holywell, with its water bursting from the ground, would have embodied fertility, purity, and regeneration. There is no doubt that the story St. Winefride resonated with people, no other Welsh saint saw English Kings coming to their shrine. The story may still resonated with people today, as the shine continues to be visited for its healing properties.

During the Middle Ages, there were many cults which were centred on wells and the belief in the power of those wells. By cults, we take the old meaning of the word cult, which meant ‘to worship’. It is therefore somewhat remarkable, that the Holywell and its buildings have survived the dissolution of the monasteries. We may be able to attribute this to the simple fact that Lady Margaret Beaufort, who was involved in funding the building, was the grandmother of Henry VIII. It may well be for this reason that the building was left intact.

We have three surviving accounts of the story of the St. Winefride, who is said to have lived in the 7th Century. Two of the accounts date from the 12th Century, and one from the 14th Century. All the accounts are similar, however we should also remember that the stories of saints lives were not necessarily supposed to be biographies as we think of them today. Their purpose was to show examples of holy living, which would inspire the population to imitate their example. It was customary for the stories to be embellished. There are many stories of the lives of female saints which fall into the category of a 'virgin martyr' legend, just as the story of St. Winefride does.