Peterborough Cathedral, Eastern England

The area that is now Peterborough, was first known as Medeshamstede. The first church here was founded in the reign of the Anglo-Saxon King Peada, in the mid 7th century, this was a Celtic Abbey. This early monastery would have followed the Celtic pattern, with a very austere life style, rigorous discipline, and continuous worship. It is thought to have been a double monastery, as 7th Century burials have been found of both men and women. The monastic settlement existed until around the year 870, when it was destroyed by Viking raiders. The church and monastic community fell into decline after the Viking invasion, and may have been abandoned.

In the mid 10th Century, Bishop Athelwold of Winchester, created and endowed a new church at Medeshamstede from the remains of the earlier foundation. The site was refurbished and extended. The new church was dedicated to St Peter, and it was surrounded by a palisade called a burgh. Soon the town surrounding the Abbey became known as Peter-Burgh, eventually becoming Peterborough.

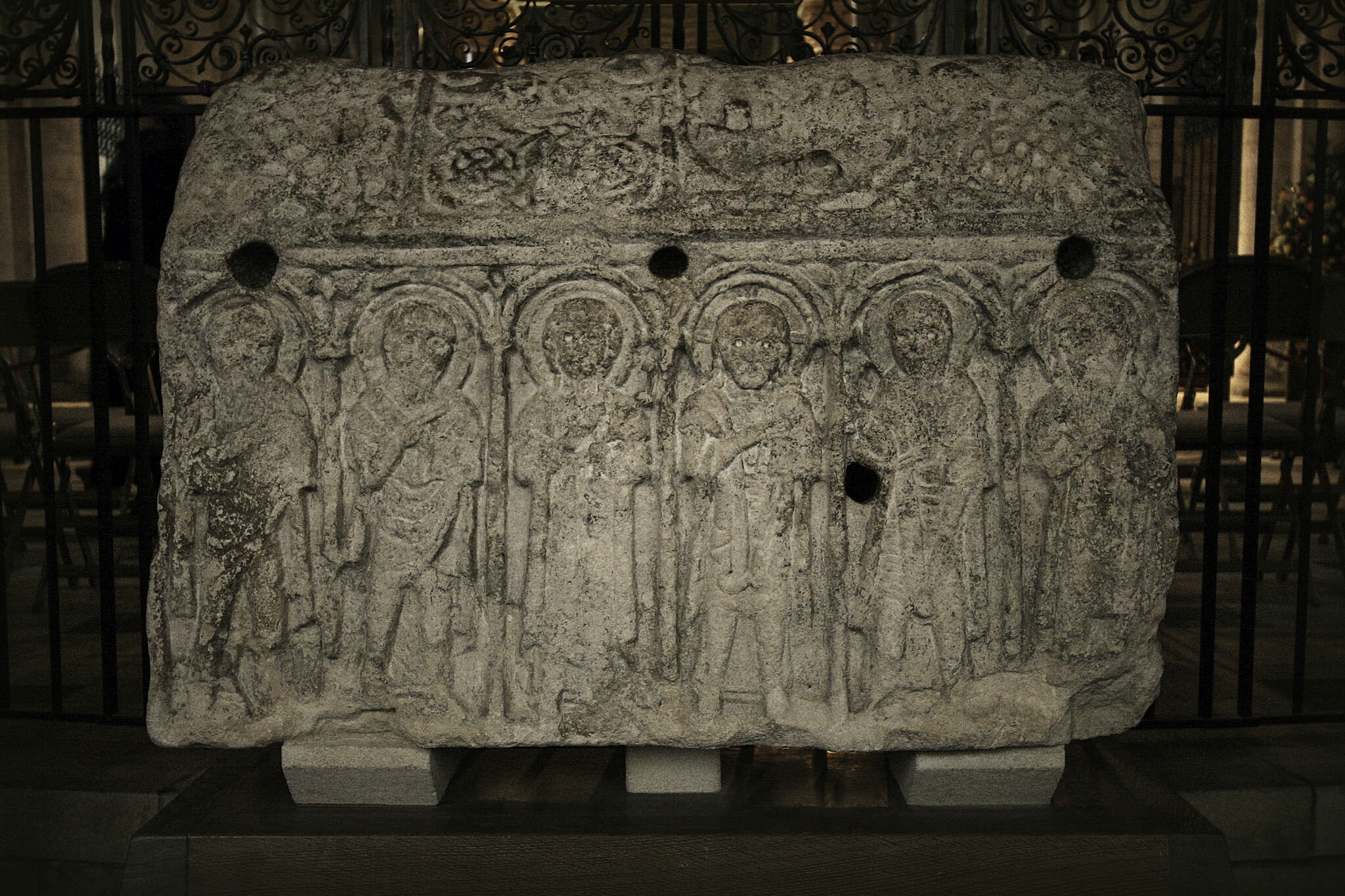

The Hedda Stone in Peterborough Cathedral, is thought to represent carvings of monks, with six on each side of the stone. This is said to have been carved to memorialise the massacre of the Abbot and monks who lived there, at the time of the Viking raid on the monastery in the 9th Century. It is thought to have been carved shortly after the raid around the year 870. Numerous sources, and one Anglo-Saxon chronicle, attribute the Hedda stone with the explanation above, but curiously, the guide book of Peterborough Cathedral does not follow this path. Instead, they offer an alternative, simply stating that the 12 figures represent Christ, Mary and the apostles, which would mean only 10 of the 12 apostles were represented, and I don’t see a figure that would be a woman on the stone, but it’s hard to tell. While I prefer the first explanation, as it makes a better story, either could certainly be correct. There is also a third possibility, that the stone itself is Roman, and was re-carved. Although the date of 870 is carved on the stone, this may have been added later. The Hedda Stone probably did at one time sit in an Anglo-Saxon church on the site, and is a remarkable survival, whatever its story.

The Church Council of Nicaea, of 787, was attended by 350 Bishops and two Papal Legates. It stipulated that no church should be consecrated without relics. Peterborough Cathedral became an early place of pilgrimage after 1070, when Brother Winegot obtained the arm of St. Oswald. Oswald’s head had gone to Durham Cathedral, but the legend tells us that Winegot and a small group of monks from Peterborough travelled to Bamburgh, where Oswald’s uncorrupted arm was kept, and they stole it under the cover of darkness. They returned to Peterborough, and a chapel was created to house the arm. Over the chapel they built a narrow tower, to allow one monk to stand over the relics and guard the artifact, 24 hours a day. St. Oswald’s arm was guarded by the monks of Peterborough Abbey. St. Oswald, in life, had been King Oswald of Northumbria, who reigned from 634 to 642, when he died in battle against King Penda of Mercia. Bede praises Oswald of Northumbria as a devout, loving King, who was concerned for his people’s welfare. He spins the tale that Oswald’s chaplain, Aidan, took Oswald’s arm and declared, ‘may this hand never perish,’ providing justification as to why the arm did not decay.

Hereward the Wake, also commonly known as Hereward the Outlaw, or Hereward the Exile, was an Anglo-Saxon nobleman, who led a local resistance movement against the Norman Conquest of England. It is possible he was the nephew of the Anglo-Saxon Abbot Brand of Peterborough. We do know that Abbot Brand supported him, which caused William the Conqueror to impose on Peterborough, the highest level of taxation of any institution, with 46 percent of the Abbey’s estates being held on a Knight’s service, depriving the monastery of almost half its income. After Abbot Brand’s death in 1069, William installed the Norman Abbot, Turoldus, but before he had even arrived, Hereward the Wake protested the appointment by raiding the Abbey. At some point in 1070, Hereward arrived with an army of Danish mercenaries, in order to prevent the wealth of Peterborough from falling into the hands of the Norman Abbot. The monks tried to withstand the invasion, but the army set fire to all the buildings and burned the town. It was said that:

‘the monks asked for peace but they did not care about anything, they went into the minster climbed up to the holy rood, took the crown off our Lord’s head – all of pure gold – then took the rest which was underneath his feet – that was all of red gold – climbed up to the steeple, brought down the altar frontal that was hidden there – it was all of gold and of sliver. They took there two golden shrines, and 9 silver cups, and they took fifteen greet roods, both of gold and of silver. They took there so much gold and silver and so many treasures in money and in clothing and in books that no man can tell another’…

The newly built church did not last long, as on the 4th of August 1116, a fire broke out in the Abbey at Peterborough. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle says that:

‘all the minster of Peterborough burned, and all the buildings except the chapter-house and the dormitory; and besides, the most part of the town also all burned.’

By 1118, a new monastic church was being built, which is the beginning of the Cathedral we see today. In 1143, King Stephen visited and stayed at the monastery. He granted the Abbey a market, which would help raise funds for the new church. The layout of the market area, to the west of the church, dates from this time. In 1154, King Henry II visited along with his Chancellor, Thomas Becket.

When the presbytery was consecrated in 1140, Bishop Alexander used Oswald’s arm in the consecration. Wether Oswald’s fame was fading, or simply because funds were needed for the new church, Peterborough Abbey was looking for a new attraction. In 1177, new relics were obtained by Benedict of Canterbury, who had witnessed Becket’s murder. He became Abbot of Peterborough and brought to the Abbey, Becket’s shirt and a stone flag, which had been stained with Becket’s blood. These alone, he did not think were enough, and so he also found a constantly replenishing supply of Becket’s blood, which were in two vials. He erected the Becket chapel, just outside the Abbey gate, where there is now a coffee house, and invited pilgrims to drink a glass of water tinctured with Becket’s blood, in return for a donation. These funds paid for the rebuilding of the nave.

From 1118, and for the next 120 years, Peterborough Cathedral was built. Today, it primarily comprises work from this time period. The church interior is primarily Romanesque, and is one of the most complete Romanesque churches to survive. The masons who worked on the Cathedral, were Durham trained, having worked on the Cathedral there. They incorporated the new technique of rib vaulting, which was invented in Durham in 1095. Abbot Benedict oversaw most of the building of the nave. Although he was familiar with the new gothic fashion, he chose not to disrupt the homogeneity of the Romanesque style, which is to his credit. In 1238, the new monastic church was consecrated, and today the structure remains primarily as it was in the 13th Century, with the exception of the west front and the new building.

There are two medieval, architectural treasures, that stand out at Peterborough Cathedral, which are unique and unparalleled. The first may be the largest, and yet the easiest to overlook, because at first glance you don’t really realise what you are looking at. When the nave was being built, between 1177- 1199, it was also being decided what would be done with the ceiling. Peterborough Cathedral contains the only remaining, English painted ceiling, from the medieval period. Although Canterbury and Norwich Cathedrals also once had painted ceilings, they were destroyed by fire. There are only three other ceilings of this type and age in all of Europe, which are at Dadesjo in Sweden, at Zillis in Switzerland, and at Hildesheim in Germany. The ceiling at Peterborough is not only unique, it is a medieval work of art.

Thomas Pownall wrote a paper for the Society of Antiquaries, in 1788, about the nave’s ceiling at Peterborough, in it he states that:

‘the ceiling is said to have been done at the time the nave of the church was built that is, at a period between 1177 and 1199’.

Pownall also spoke to the then Bishop, John Hinchcliffe, who in turn had spoken to the man who had repaired and cleaned the ceiling, 30 years previously. The unnamed man had told him that several of the figures on the painting were encrusted with dirt, but that on wiping them with a sponge, they became clear and bright again. He concluded that the last coat on the ceiling, was oil or varnish. He had assured the Bishop that he only retraced the figures, except in one instance, in the third or fourth compartment from the west door, where the whole figure peeled off. In this single instance, he used his imagination, but imitated the style of the rest. The Bishop said he had no doubt as to the reliability of the man’s statement. It is very likely that we have this unnamed man to thank for the survival of the medieval artwork on the ceiling of the Cathedral. How many people then would have the integrity, and respect, for the previous work, to restore it and not just paint over it with some “improvement”. The above account is reassuring, and helps us to know that what we are looking at is genuinely medieval artwork. We are also lucky, that nobody seems to have done any work on the ceiling before 1743, and that it has been preserved.

The theme of the medieval ceiling, in the nave of Peterborough Cathedral, is thought to be one of power. The power through which God created, and ruled the world. So, we have depicted, an equal mix of Kings and Bishops, which take pride of place on the ceiling. There are also pagan symbols to be found, far more than we would see in a work from the later Middle Ages. The ceiling itself is 62 meters (205 feet) long, and 11 meters (35 feet) wide. It has 20 centre lozenges, each with painted figures, and there are 19 down each side with alternating leaf patterns.

One section of the ceiling shows, from left to right, St Paul, wearing a red robe, holding a sword and a book, next to him is a King holding a sceptre and a lamp, he is flanked by musicians below. Next there is an Archbishop, holding a cross staff and a book, and next to him, another King with a sceptre, who points upwards. Finally, there is another Archbishop, who is also pointing with one hand, while holding a book in the other. Perhaps medieval man could identify them individually, at least while their eye sight remained sharp, as these are 80 feet above the viewer’s head.

The Cathedral nave’s ceiling is made from oak boards, which have been laid edge to edge, and fastened to a network of trusses, which are nailed from below. During the restoration work of 1834, bolts were put through many of the boards, to secure the ceiling to the roof trusses, which was a very harsh and destructive way of dealing with an issue. When it came to the 1920’s restoration, Death-watch beetle had moved in, and threatened the wood of the ceiling itself. This can only happen if there is a high moisture content, and it is likely that neglect caused the conditions which allowed for the infestation. During this restoration, screws were inserted from above to support the ceiling, but this prevented the natural movement with changes in temperature, and caused many of the boards to split. This shows why it is so important to get restoration correct, as a massive amount of damage is caused when we get it wrong, and try to improve something that doesn’t need improving.

By the 1990’s, scaffolding was erected to inspect the ceiling. This found structural problems, with the boards splitting and paint flaking. As a result, work began on its restoration again, in 1997, this included the painting, cleaning and rehanging of the whole ceiling. This was a massive project when you consider that the area of the painting itself is 1/6th of an acre, 800 years old, and suspended 85 feet in the air. Dendrochronological dating was carried out by the University of Sheffield, and proved that the oak used in the painted panels is a slow grown type, which came from North Germany. The felling date was around 1240. The joints which are still original, have been dated to 50 years earlier.

The second, uniquely medieval feature at Peterborough Cathedral, is the west front. Its type is entirely unique in Western Europe. The three giant arches are 26 meters high (85 feet), and may have been inspired by the original west front of Lincoln cathedral, which had five recessed arches. The west wall, within the arches, is enriched with various arcades. In the opening of each arch, is a doorway with a window above.

At the top of the west front is the eroded figure of St. Peter, which dates from around 1220, he sits in the apex of the central gable. Apparently, he dropped his keys in 1923, luckily there wasn’t anyone below at the time. In the two side niches below, are the figures of St. Paul and St. Andrew. The Abbey church was dedicated in the names of all three of these saints, in 1237. The small niches, are thought to have once contained figures of the six kings of England since the Norman Conquest, as there had only been 6 kings from the Conquest, when the west front was built. The west front of Peterborough Cathedral was built to house thirty statues. What remains of the statues are all in very poor condition, so much so, that it is now difficult to identify the figures.

There seems to have been several changes to the design. The Perpendicular porch in the centre, was added in the late 14th Century, because the central arch had developed a forward lean. The porch insertion works as a wedge, to prevent further movement.

The monks at Peterborough Abbey needed a way of keeping time, in order to observe their daily services. Previously, they had done this with the use of sundials and by ringing bells, but a new way of timekeeping was emerging. The earliest clocks have no face as we know it, but instead they would strike every half hour. The one at Peterborough has survived the test of time and is still in working order. The wooden frame and earliest parts of the mechanism, date from the mid 15th Century and are painted black. In 1687, a local clockmaker added a more accurate pendulum and other parts, which have been painted green. In 1836, a new mechanism was installed on top of the frame, and this was painted in blue. The clock was still in use in the bell tower until 1950, when it was replaced by an electronic device.

The list of visitors to Peterborough Abbey, reads like a 'who’s who' of medieval England. Edward I visited in 1302 and stayed for several days, costing the Abbey £245 to feed him and his entourage. This would have been the equivalent of a years income. In 1314, Edward II visited with his army, on route to Scotland and the Battle of Bannockburn. Edward III spent Easter at the Abbey in 1327, and his son, Edward, the Black Prince, spent the summer there in 1337.

In 1461, the town of Peterborough was sacked by the Lancastrian army, led by Queen Margaret of Anjou, during the Wars of the Roses. The monastery was not far from Fotheringhay Castle, which was the main seat of the rival claimant to the throne, Richard, Duke of York.

Katharine of Aragon, the first wife of King Henry VIII, is buried at Peterborough Cathedral. Born in 1485, she was the daughter of King Ferdinand of Aragon, and Queen Isabel of Castile, two of the most powerful monarchs in Europe. From the time of her birth, she was destined to be a Queen. At the age of 16, she married Arthur, the Prince of Wales, who died shortly after their marriage. She then married King Henry VIII in 1509, they had only one surviving child, the Princess Mary. Having failed in her duty to provide an heir, Henry VIII wanted a divorce, but it was denied by the Pope. He eventually broke from Rome and created the Church of England, divorcing Queen Katherine in the process. When she died, she was buried as his brother’s wife, with no reference to her having been Queen of England for 24 years.

The section of the Peterborough Cathedral known as the 'new building,' was the last major part of the Abbey. It was commenced in 1438, but the building was built between 1496 and 1508. The new building created space for processions behind the High Altar, and now forms the eastern end of the Cathedral. It is also a particularity fine example of the height of Perpendicular architecture, with large windows and a beautiful fan vaulted ceiling.

The Master Mason who is thought to have been responsible for the new building work was John Wastell, he also built the vault in King’s College Chapel in Cambridge. Abbot Robert Kirkton had commissioned him to do the work. It was only shortly after the work was completed, that Abbot John Chambers surrendered the Abbey to the King’s Commissioners in 1539, but luckily the building was preserved as a Cathedral in 1541.